How many significant scientific discoveries can you think of? And how many of those discoveries came about by accident, because someone was exercising his or her curiosity? This blog post is a celebration of the anniversary of one such discovery being patented more than 160 years ago. It’s a discovery that continues to have significance right up to the present.

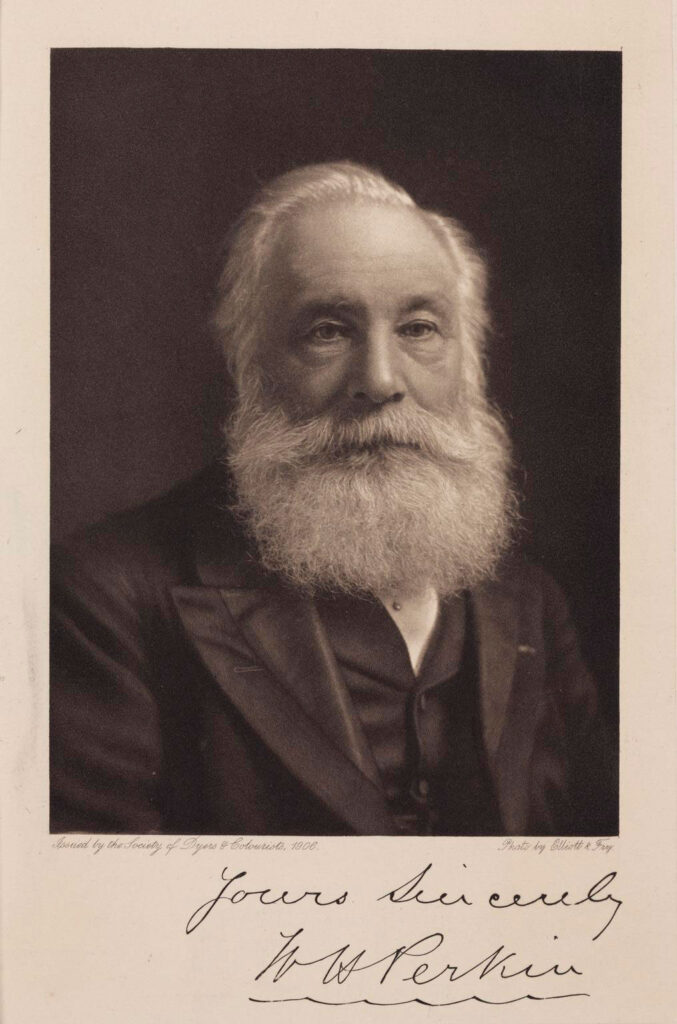

One of my favourite collections held in the archive at the Museum of Science and Industry is a loan from the descendants of Sir William Henry Perkin. Perkin was a research chemist, and a curious experimenter from an early age.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

I love the Perkin Collection because its contents tell a story of an accidental discovery changing the way things were traditionally done in one industry, and leading to an entirely new industry being established. It’s also a story about how making use of an inquisitive mind can change someone’s fortunes.

In 1856, during the Easter holidays from college, Perkin worked on a task set for him by the head of the Royal College of Chemistry, August Wilhelm von Hofmann. Only 18 years old, Perkin was in his second year of working as Hofmann’s research assistant. Hofmann was keen to develop a synthetic form of quinine, which was in demand as a treatment for malaria. Hofmann was interested in the chemical synthesis of natural compounds, and thought quinine was a good challenge, given that its natural form was difficult to extract.

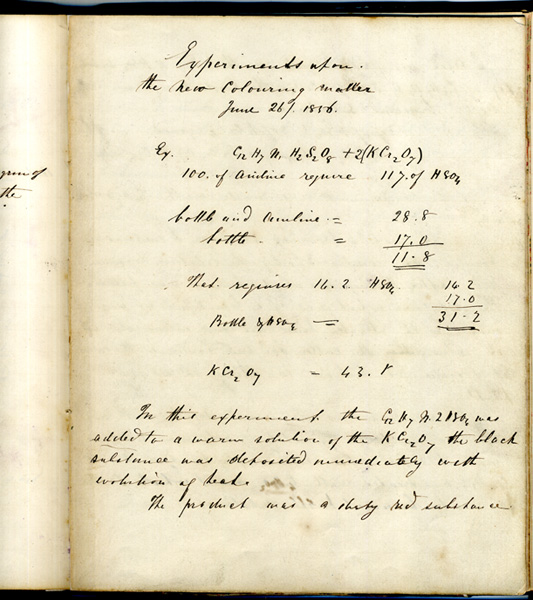

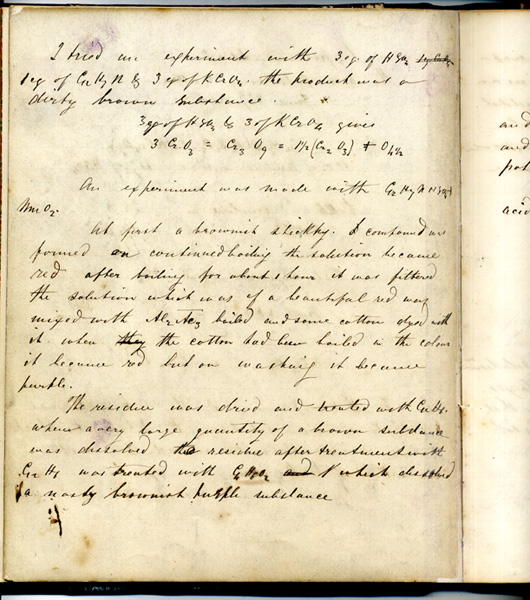

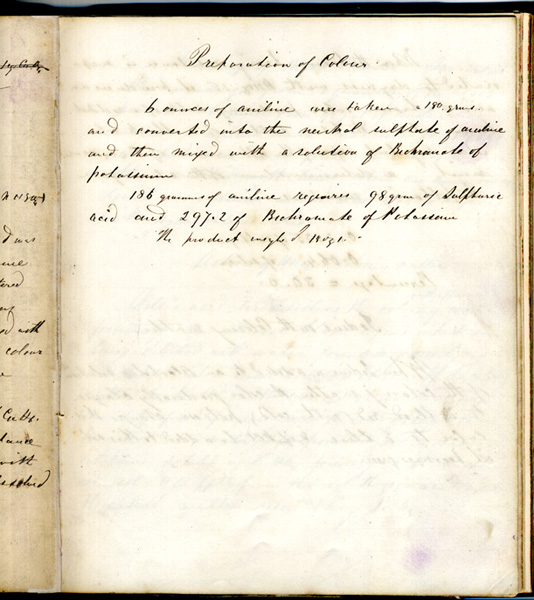

Perkin’s task was to carry out experiments using a substance called aniline, a colourless aromatic oil derived from coal tar. Perkin worked on his task in a rudimentary laboratory at home. His experiment involved him oxidising aniline using potassium dichromate. The oxidisation produced a black precipitate that, when the colour was removed, dyed silk purple. He recorded his findings in a notebook, which the museum holds on loan from the City of London School.

Above: Perkin’s laboratory notebook for 1855-1856, pages showing experiments on mauveine in June 1956. Note the purple fingerprints on the pages.

Perkin called the colour mauve and named his unique synthetic dye mauveine. You can see Perkin’s fingerprints in mauve on some pages of his laboratory notebook.

The discovery changed the dyeing industry and made Perkin’s fortune. It also helped to establish the modern chemical industry. After Perkin’s pioneering use of a coal tar derivative to make synthetic dyes, coal tar ceased to be a waste product only good for waterproofing fabric. Other derivatives of coal tar were used in saccharine production, the pharmaceutical industry and the development of perfumes. Perkin was able to retire from business aged 36, and spent the rest of his life carrying out research in other areas of chemistry.

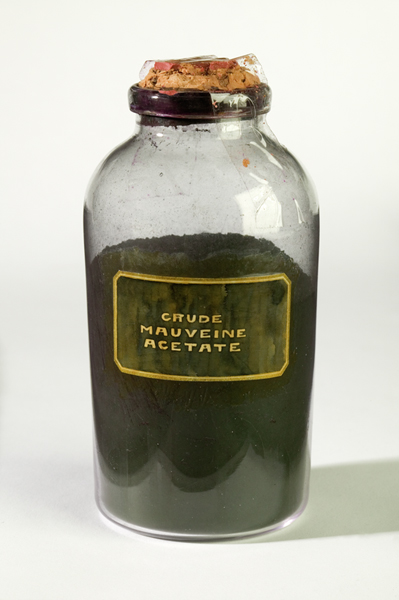

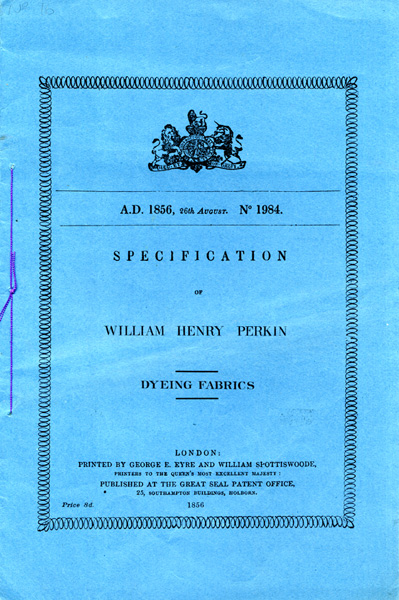

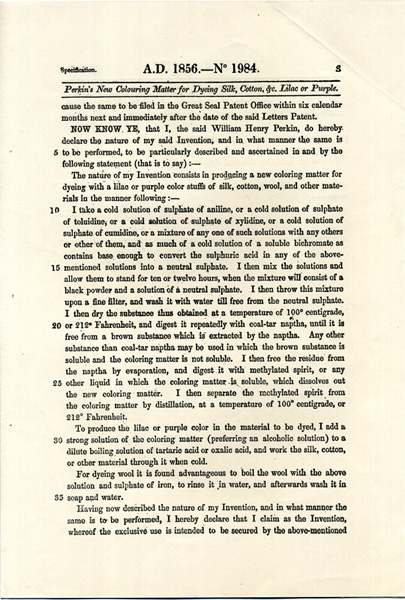

Perkin took out a patent on his accidental discovery on 26 August 1856. Mauveine, or aniline purple as it is more formally known, was the world’s first synthetic dye and was among the first mass-produced chemical dyes. The Perkin collection includes four copies of the third edition of Perkin’s patent, as well as a bottled sample of the dye prepared by Perkin in 1862. The patent records Perkin’s method for making aniline purple dye.

Excitingly for the museum, a researcher at the University of Aberdeen contacted us in 2012 about his research into how mauveine was made. Dr John Plater is an organic chemist, and he was curious to know whether the aniline purple dye used in textiles and stamps produced in the years following the granting of the patent had the same chemical structure as aniline purple synthesised using Perkin’s patented method.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Dr Plater used a sample of the bottled dye held at the museum, with the permission of the collection’s owners, to analyse its structure by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. He did the same with the lilac coloured sixpenny stamps produced using Perkin’s mauveine in the 19th century. When he compared his results, he found something unexpected. Sir William Henry Perkin had been keeping something secret. In continuing to research aniline dye synthesis, Perkin had developed ways of producing aniline purple by varying its key components, but he didn’t want his competitors in France and Germany to know.

Dr Plater believes that the changes Perkin made are linked to the mass-production of the dye. One change in particular increased the amount of dye that could be synthesised and was a major leap forward in synthetic dye production. Dr Plater published his research findings in the Journal of Chemical Research in November 2016. You can read an interesting article about Dr Plater’s research in the January 2017 issue of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Chemistry World magazine.

We love it when our historical collections are used to further contemporary knowledge about science and technology. Now, what accidental discovery are you going to make that might change the world? Or what might you find in our collections that will inspire you to make a discovery of your own?

3 comments on “William Henry Perkin and the world’s first synthetic dye”

Comments are closed.

I think you should also talk about the risks associated with aniline dyes. Socks made with aniline dyes inflamed men’s feet and gave garment workers sores and even bladder cancer.

Hello Heather,

Thank you for your very interesting post, please can you tell me if you know of any other garment making which caused a similar reaction and in what era.

Thanks.

A synthetic dye made before aniline purple was Paris Green, made in 1814, recipe published in 1822