Please note: Robots ended on 15 April 2018. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

Our volunteers are awesome

Well we knew this anyway, but we wanted to take this opportunity to day a huge THANK YOU! to our team of volunteers who gave an amazing 2,450 hours of their time over the duration of the exhibition.

Our volunteers did a fantastic job of engaging visitors with Robots, showing visitors how to interact with our robots and running handling sessions so that you guys could get up close and personal with the androids.

The South Koreans might have gone all out with robots to help visitors at the Winter Olympics, but we’ll take human helpers over android assistance any day.

You *loved* the exhibition

We had 66,826 visitors to our Robots exhibition from October to April, which absolutely smashed our original visitor target of 46,955.

We were particularly pleased with the family trail created by our Creative Content Developer Adam Flint, in conjunction with our colleagues at the Science Museum.

The trail really helped to make a complex topic in a fairly ‘adult’ exhibition relevant and fun for our younger audiences and walking through the exhibition and seeing families do the robot dance was a definite highlight!

We’ve all probably used chatbots without realising it

Chatbots have been heralded as the next big thing in artificial intelligence. If you’ve ever used a text or web chat, you’ve probably used a chatbot. But what exactly is a chatbot? How do they work? And should we be scared of them?

Generally speaking, we’re not keen on robots that look like us

Our creepy baby robot generated a lot of comments from you guys, and most of them weren’t very complimentary:

“The robots were amazing and the baby was very creepy”

“Pepper was cute, not sure about the baby, was a bit freaky”

But why did the robot baby generate such a strong reaction?

It’s all about the uncanny valley, as mentioned in an earlier blog.

The uncanny valley describes the dip in emotional response when we encounter something that appears to be human but isn’t quite ‘right’. The more we encounter the ‘human’ in something that isn’t human, the stranger we find it.

Hypothesised in the 1970s by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori, the uncanny valley usually relates to robots, but can also apply to life-like dolls, computer animations and some medical conditions.

Most people liked our Pepper robot because it was cute but looked distinctly ‘robotic’, whereas the baby robot freaks us out a little because it looks a lot like us but isn’t quite ‘us’.

The idea of robots has been around for a REALLY long time

The premise of the exhibition was that automation and robotics have been around for over 500 years, but discovering that robots had been envisaged over 3,000 years ago blew my mind.

At the In Conversation: Robo Sapiens event in January, Dr Adam Rutherford (of Radio 4’s Inside Science fame) gave two examples of robots being imagined in Homer’s Iliad, which is over 3,000 years old.

In the story, Thetis goes to Hephaestus to ask him to make a replacement set of armour for her son Achilles and finds him ‘hard at work and sweating as he bustled about at the bellows in his forge.’

Homer imagines:

He was making a set of 20 tripods to stand round the walls of his well-built hall. He had fit-ted golden wheels to all their feet so that they could run off to a meeting of the gods and return home again, all self-propelled—an amazing sight.

Homer then goes on to describe a gynoid:

Waiting-women hurried along to help their master. They were made of gold but looked like real girls and could not only speak and use their limbs but were also endowed with intelli-gence and had learned their skills from the immortal gods. While they scurried round to support their lord, Hephaestus moved unsteadily to where Thetis was seated.

Robots! In Ancient Greece! Sort of.

Trying to make a robot that walks on two legs is difficult and unnecessary

Our exhibition charted the last 500 years of us trying to recreate ourselves in robotic form, with varying degrees of success.

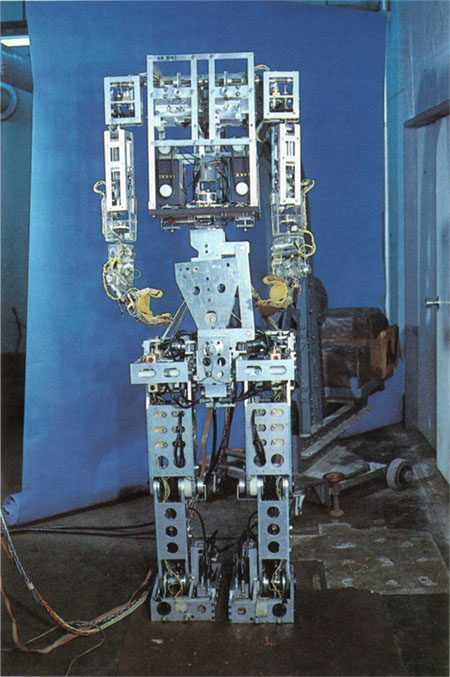

In 1970, Japanese engineers developed the WABOT-1, the world’s first full-scale anthropomorphic robot. It was able to communicate with a person in Japanese and to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial ears and eyes and an artificial mouth.

The WABOT-1 walked with his lower limbs and was able to grip and transport objects with hands that used sensors.

However, the movement was quite jerky, and various creations after the WABOT-1 have proved that it’s very difficult to create a robot that walks like we do. Humanoid robots are a vanity project: an attempt to create artificial life in our own image—essentially trying to play God.

But why bother? We can’t fly, we’re not very good swimmers, we can’t live in a vacuum and if we want to travel more than a mile, most of us will get in/on some type of wheeled vehicle.

Bipedal locomotion has served us well but it is limited and requires a huge amount of brain power and years of learning to perfect. The computer versions of our brain are nowhere near our level and are unlikely to be so for decades to come.

After nearly 100 years of development, our most advanced humanoid robots can only just open a door without falling over (too often).

So why not make a robot that fits in with the environment that it’s been designed for? Boston Dynamics have recently developed a robots with wheels and legs called Handle, which has been designed to pick up heavy loads and move quickly with them in tight spaces, which is perfect for a warehouse environment.

To read more about the future of robotic design, read our blog post.

We won’t be having cyborg babies anytime soon

Mainly because human battery life is far superior to that of a robot. And apparently that’s the main reason.

AI is getting smarter, and learning how to learn…

AI is still very much in its infancy, as we’re not really ‘there’ yet with transferrable knowledge. A robot can learn a task and become absolutely world class at performing that task, but it then can’t apply that learning to a new task in a way that a human can.

However, in March 2016 Google’s DeepMind AlphaGo beat the world’s reigning human Go player. During the games, AlphaGo played a number of highly inventive and surprising moves that overturned hundreds of years of received wisdom about the game.

The creativity that AlphaGo displayed wasn’t learnt from a human, it was learnt from principles it taught itself over thousands of hours of playing the game. This is data representation from learning, which is a new concept in AI.

Sweet dreams…

One comment on “Things we learnt about Robots”

Comments are closed.