Until his project, this archive had been virtually unexplored, and little was known about Langworthy’s story. Alexander’s research will help to enable the museum to tell richer and more wide-ranging stories about Manchester’s textiles industry and its global connections in future galleries and exhibitions.

As a Collaborative Doctorial Partnership student, I have been given the opportunity to research the rich archives belonging to Manchester textile firm Langworthy Brothers and Co., which are held at the Science and Industry Museum. The aim of my PhD research is to shed new light on the people, skills, processes and networks involved in the buying and selling of Manchester-made textiles in the early to mid-19th century, particularly on a global scale. This has been less well explored in comparison with Manchester’s manufacturing history. The research aims to create a more wide-ranging narrative of Manchester’s textiles history, and some of my findings will be showcased as part of the future Cottonopolis gallery at the museum.

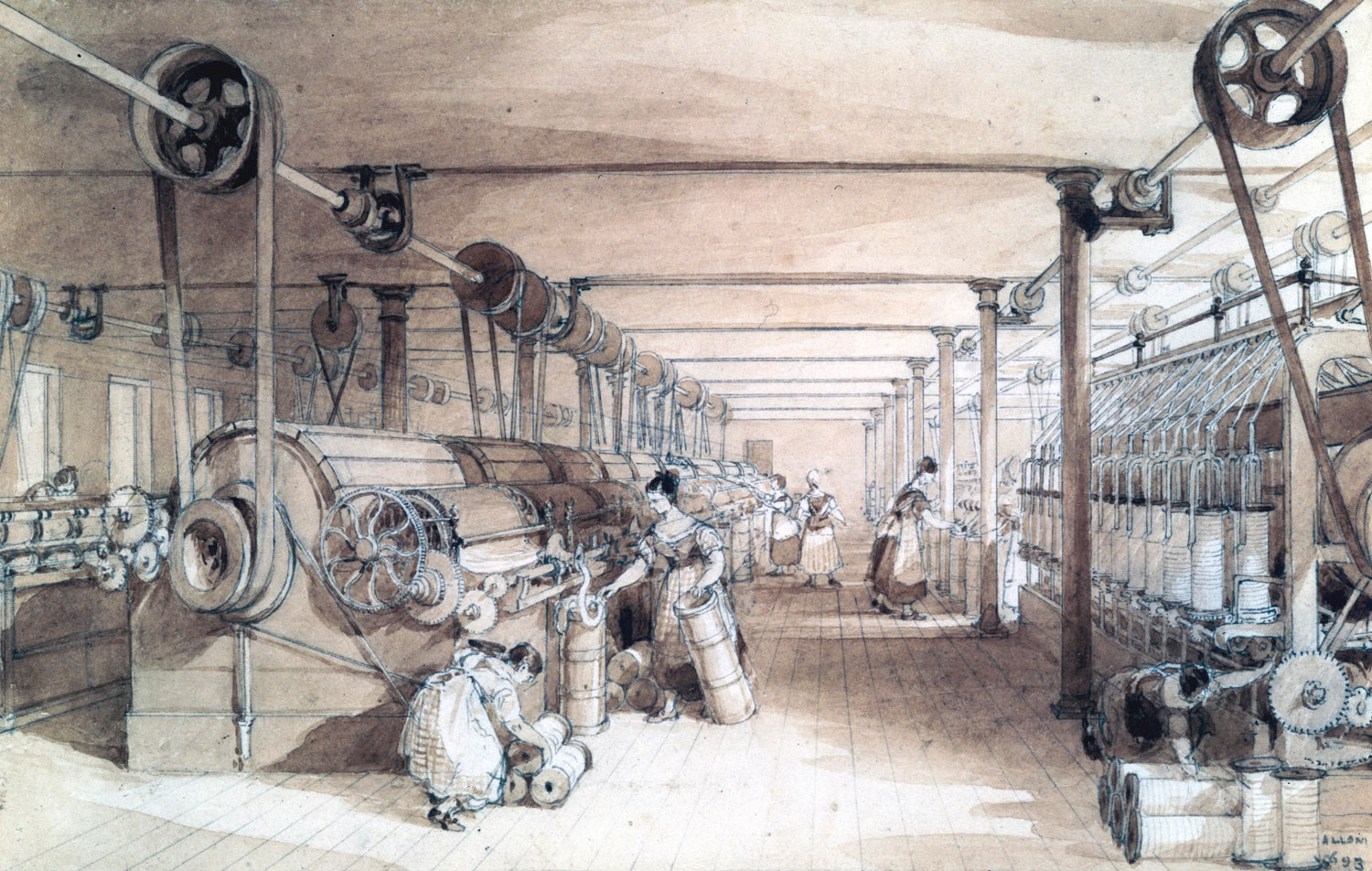

From about 1780, Manchester began growing into the shock city of the Industrial Revolution, a place where new ways of working were generated in its innovative cotton mills. The textiles industry was the first to be mechanised, and ground-breaking machines and new forms of power were applied to the task of transforming raw cotton into yarn and cloth.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

However, alongside this innovation came exploitation. Most of the raw cotton used in Manchester’s mills was grown by enslaved African people who were forced to work on plantations in the Caribbean, South America and the United States.

After about 1820, cotton manufacturing began spreading out to Manchester’s surrounding towns, with the centre of Manchester becoming chiefly a place where cotton textiles were bought and sold. This earned Manchester the title of ‘Cottonopolis’, on account of its central role as the merchanting centre of Lancashire’s textile industry.

Hundreds of textiles businesses were clustered in and around Manchester, responsible for the manufacturing and merchanting of yarn and cloth. The architectural legacy of these textile firms can be seen all around the city today. If ever you find yourself walking through Manchester and you have some time to spare, look at the buildings around you. Many were once warehouses that belonged to merchants and manufacturers involved in the textiles trade. It was in these buildings that they stored and packaged stock and prepared it for sale.

Billy Wilson CC BY-NC 2.0.

Langworthy Brothers and Co. were one of these hundreds of textiles firms. They traded in Manchester from the early 1820s into the 1960s. Over the course of their existence, the firm was involved in spinning, weaving, dyeing and printing textiles. They were also heavily engaged in the merchanting and export of textiles all over the world. They were a member of a small set of firms that were able to successfully conduct both merchanting and manufacturing simultaneously. However, very little of their story has been explored until now.

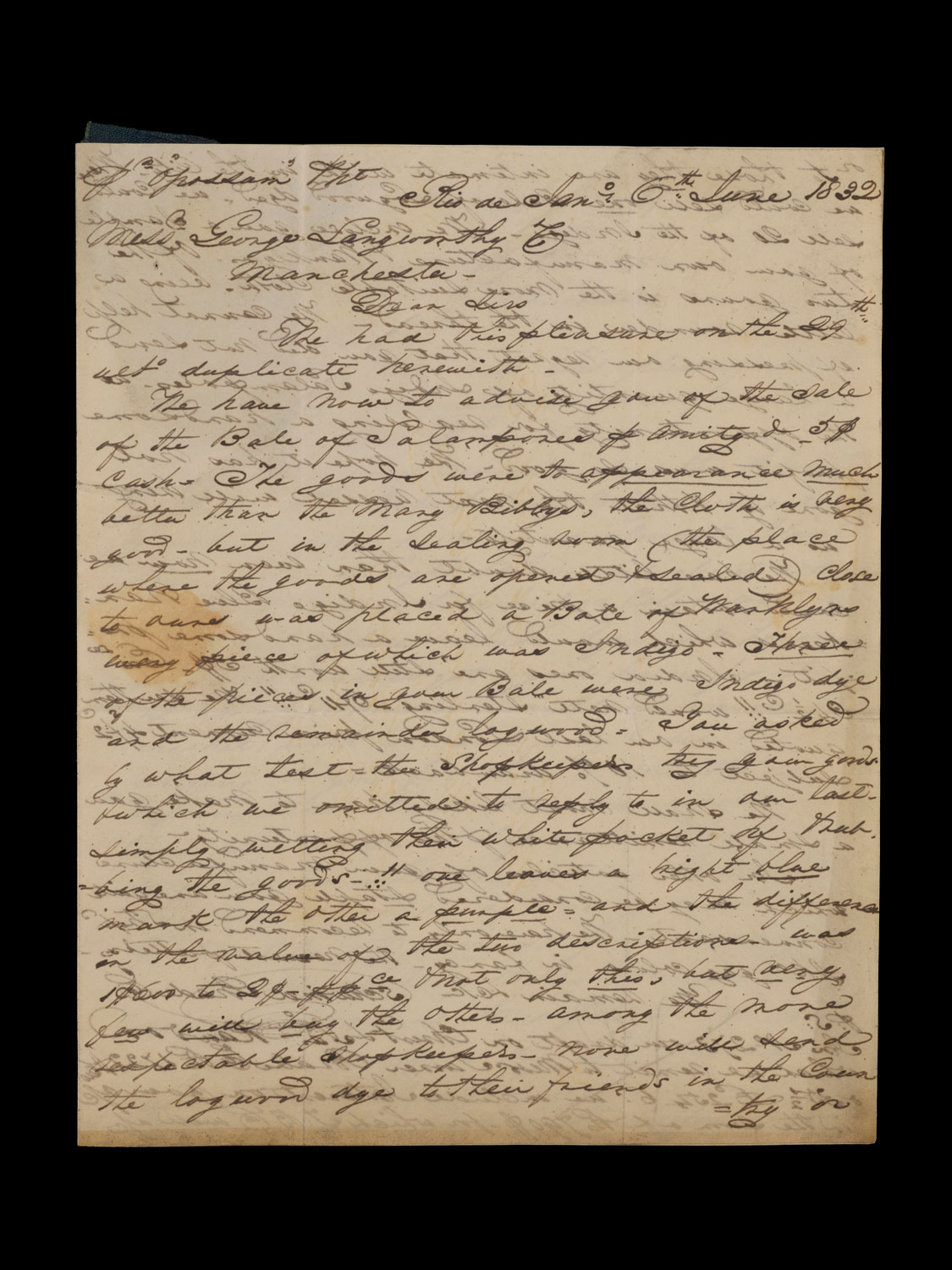

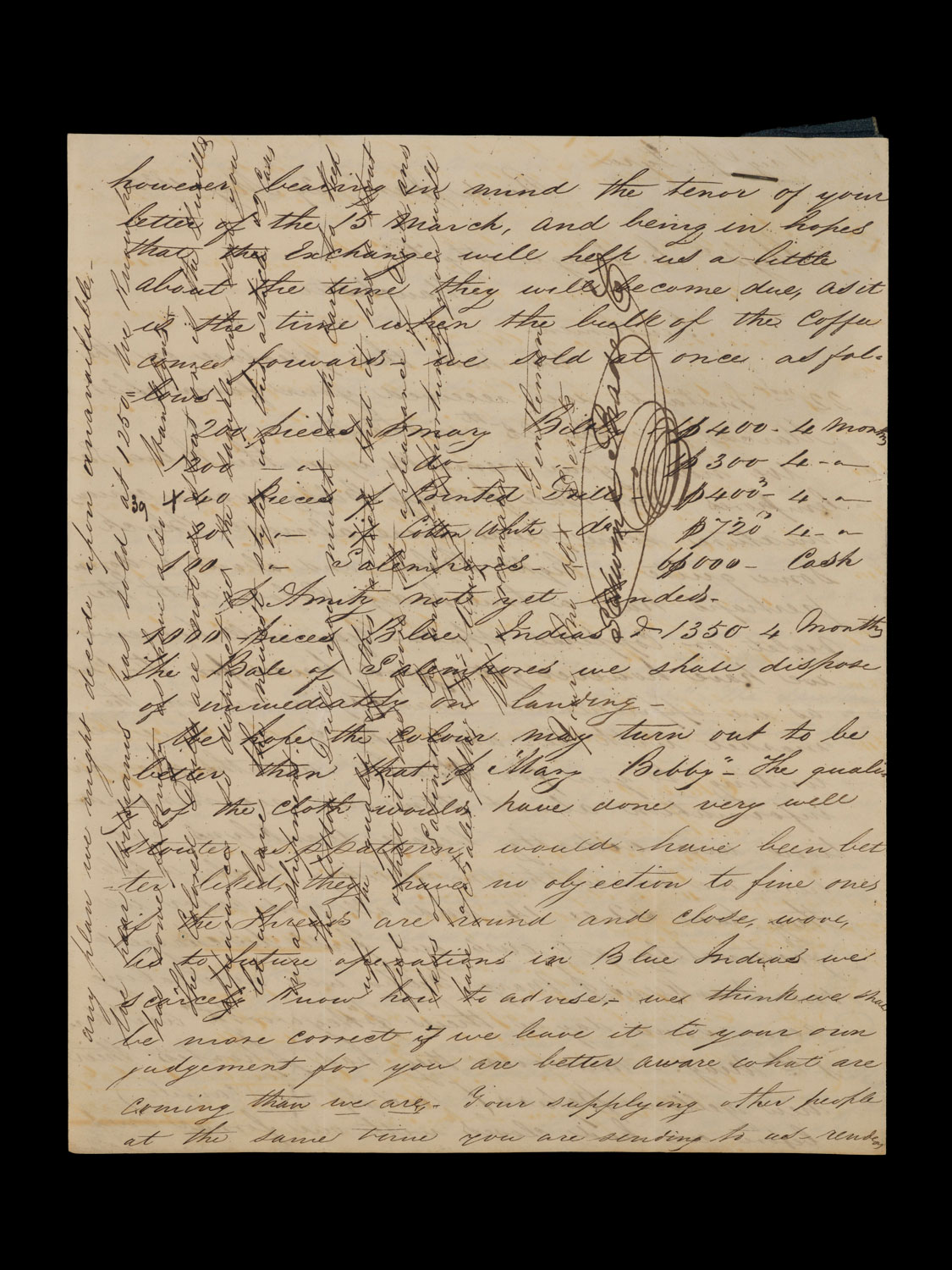

Langworthy’s business archive is impressive on account of the rich volumes of correspondence it contains, which were passed between Langworthy in Manchester and numerous other firms dotted around Britain and the globe. Because of the diversity of the firm’s activities, elements of almost every aspect of Manchester’s textiles industry are documented in the records, giving us a unique snapshot into the early beginnings of a complex global trade.

The Langworthy brothers, George, Edward and Lewis, were the sons of a London-based merchant family that had originated in Somerset. George moved to Manchester when he was old enough to take part in the northern manufacturing scene while Edward and Lewis spent some time abroad as merchants for other firms. By the mid-1830s, Lewis and Edward returned to England and joined George in Manchester to form Langworthy Brothers and Co. By 1838, the firm had purchased a huge manufacturing complex on the banks of the River Irwell in the Greengate area of Salford. Eventually, the mill had over a thousand people working there. Today the mill has been demolished and is no longer visible, however, in 2011 over 40 tonnes of stone that belonged to the mill were excavated from the river.

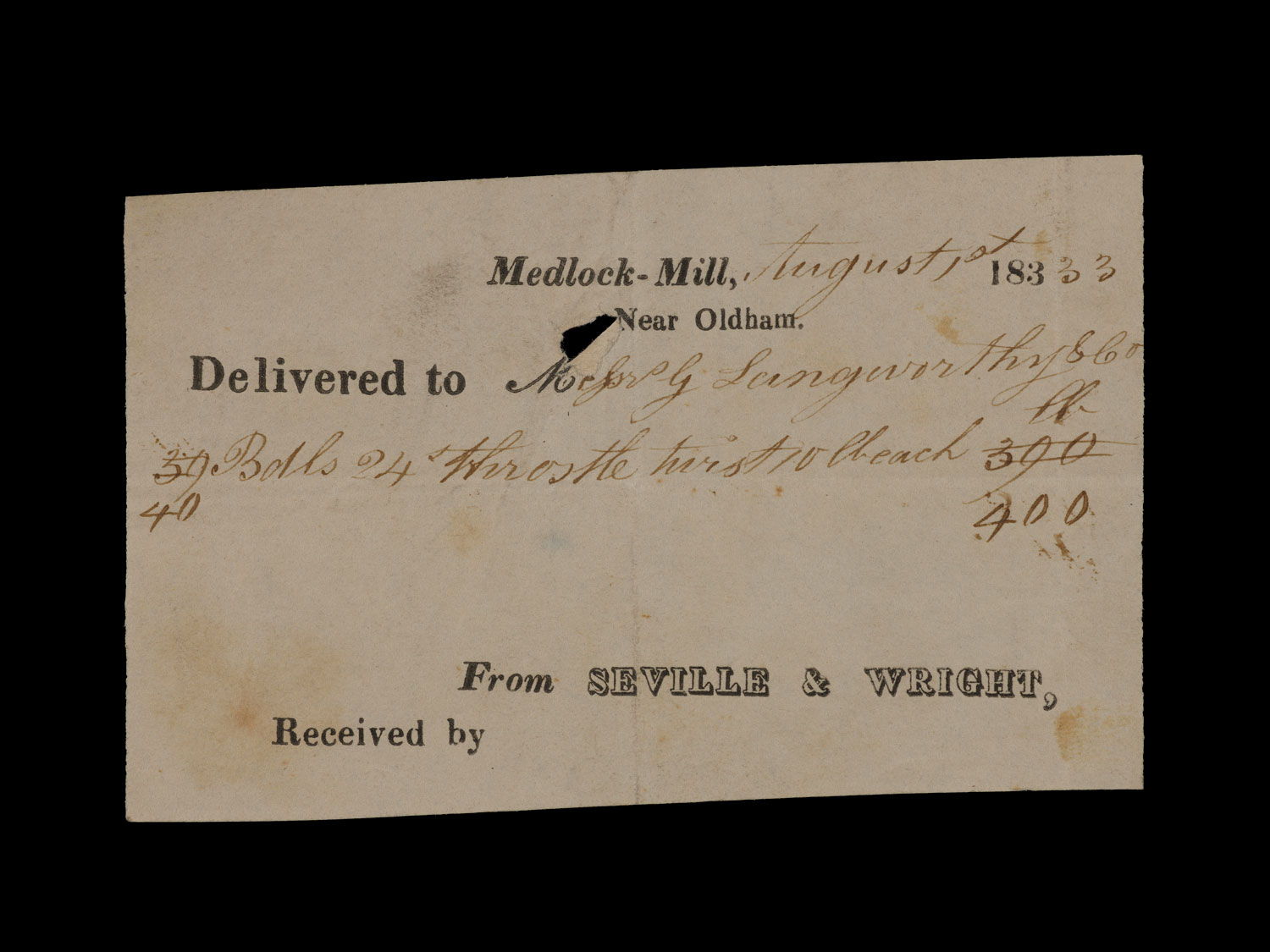

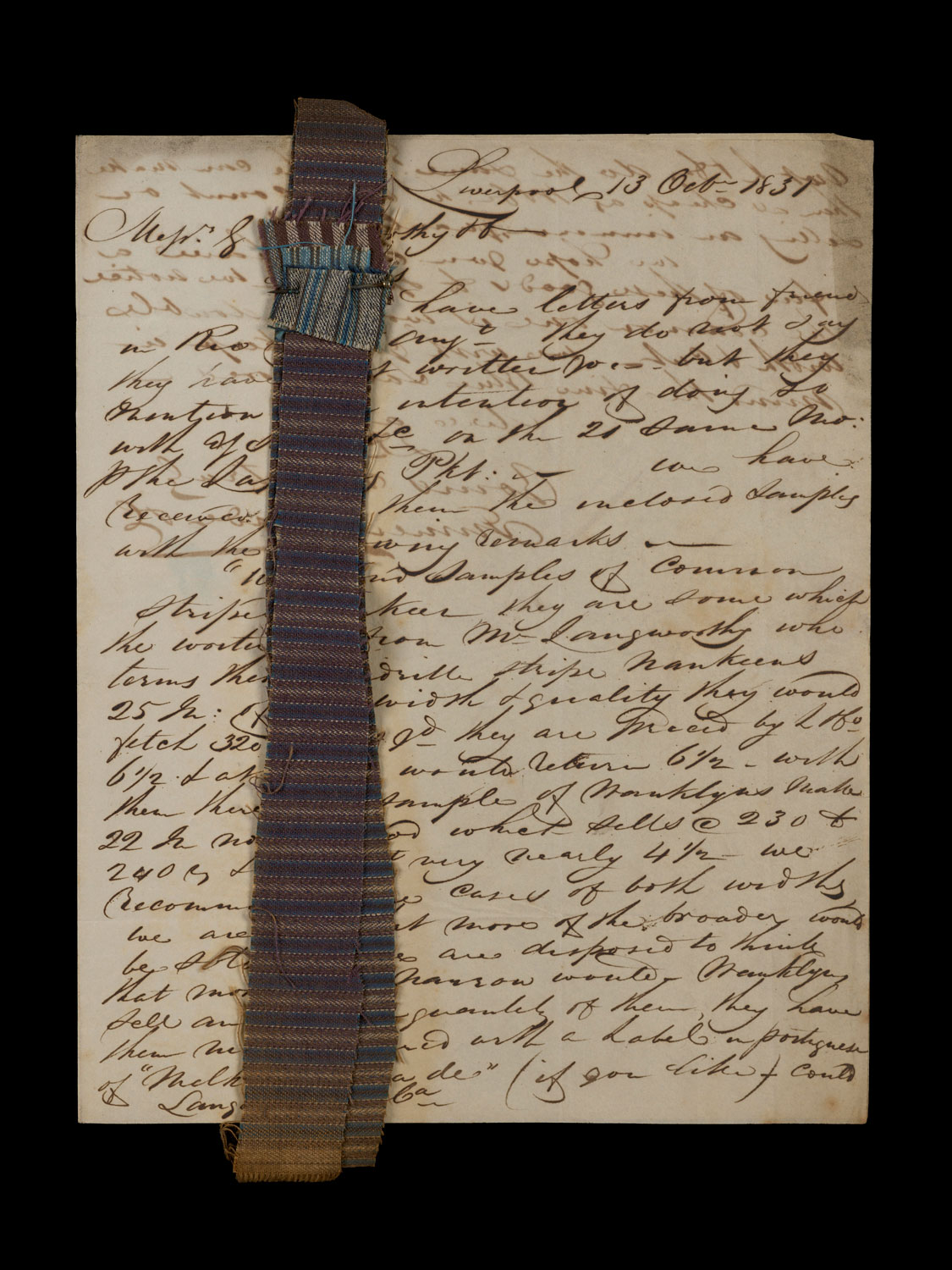

With their main headquarters on Cannon Street in Manchester, Langworthy sat right at the heart of the business community. Today the street no longer exists and has been built over to create Manchester Arndale shopping centre; however, it stood not far from Market Street, another of Manchester’s most important sites for business premises. Langworthy were originally manufacturers of nankeens, a yellowish cloth that was commonly used to make items of clothing like trousers. At the same time, they also produced many other types of cotton products such as cotton drills, a durable fabric with a diagonal weave, and ginghams, a checked fabric. The correspondence in the archive shows that Langworthy purchased material like yarn from local spinners such as Seville Wright and Co., who were located near Oldham. They used these materials in their own manufacturing process.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Langworthy also sourced finished goods to sell from firms in Leeds and Glasgow. It was their Leeds connections that placed them in contact with influential merchant banks based in London. These connections allowed Langworthy to trade to scores of traders dotted around Latin America, in Chile, Mexico, Argentina and Cuba. However, it was their Brazilian trade that is most noticeable in the archives at the museum.

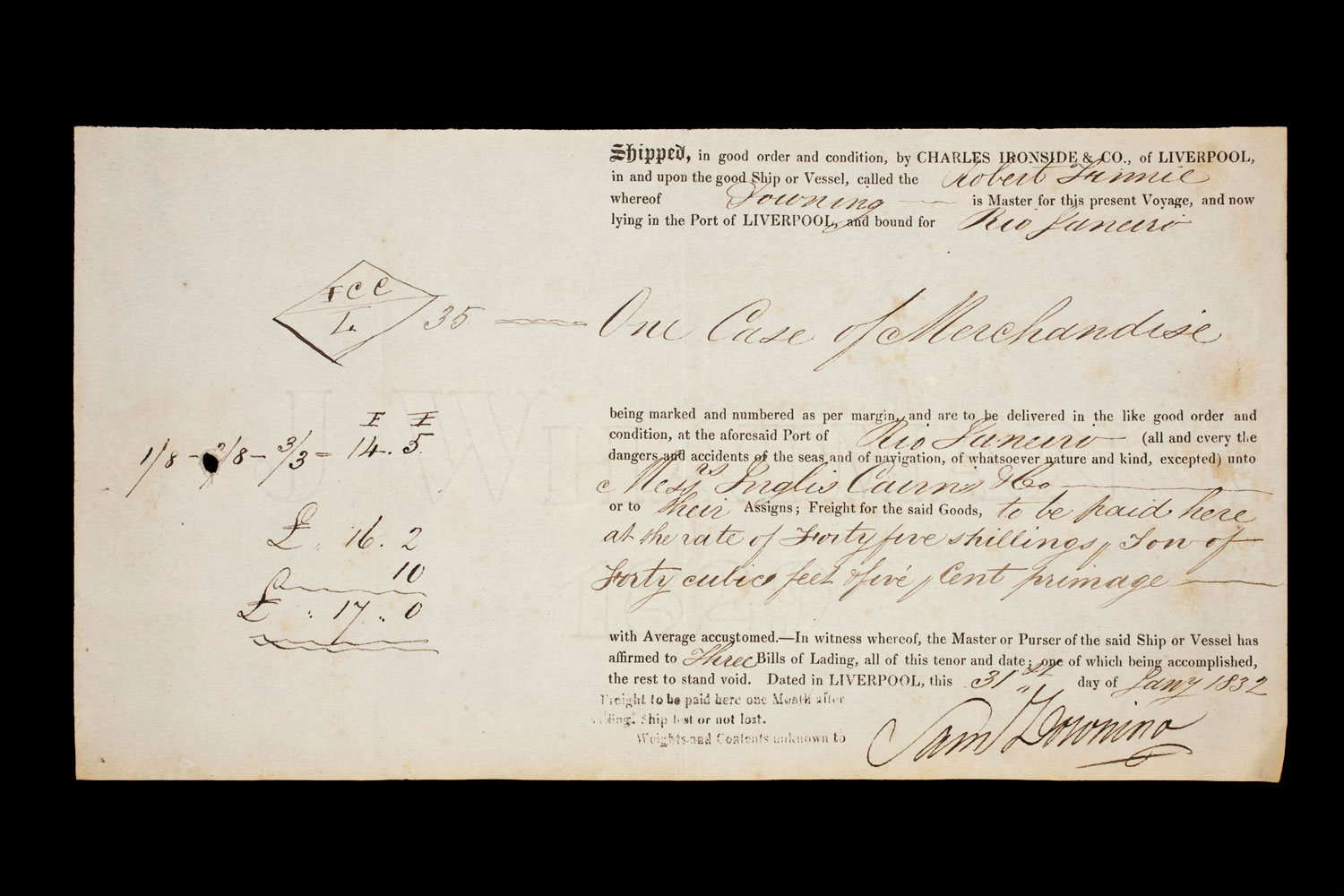

Brazil had become independent from colonial Portugal by around 1824. The country’s independence from that empire opened its market up to foreign merchants. British textile merchants seized the opportunity to send their goods to ports on the Brazilian coast. For Langworthy, it was the Rio De Janeiro and Salvador ports that provided the gateway to their trade in Brazil. Their connections with agents in these ports were secured through Liverpool merchants.

Langworthy’s trade with Brazil reveals an important but underexplored story of exploitation. During the time Langworthy were trading, Brazil’s economy was heavily underpinned by slavery. More African people were trafficked to Brazil than to anywhere else in the Americas—about 4.6 million people in total. The Bahia region, where Langworthy’s main buyers were located, was a region highly populated by enslaved African people, many of whom were forced to work on plantations producing valuable goods like coffee, sugar and cotton, which were then exported to Europe.

Langworthy’s Manchester-made textile products were supplying this slave economy. The types of textiles they sold were diverse and it is likely they would have been worn by many different types of people, including both enslavers and those who were enslaved. In exchange for their textile goods, Langworthy often imported raw cotton that had been grown by enslaved people on the plantations of Brazil, which they handled through brokers in Liverpool. They also imported other goods produced by enslaved people, such as coffee. Many of the other locations Langworthy sent their cloth were also engaged in slavery, such as Cuba and the southern United States. As the archives reveal, much of Langworthy’s trade, and indeed Manchester’s textiles industry more widely, was intertwined with this terrible system of human exploitation.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

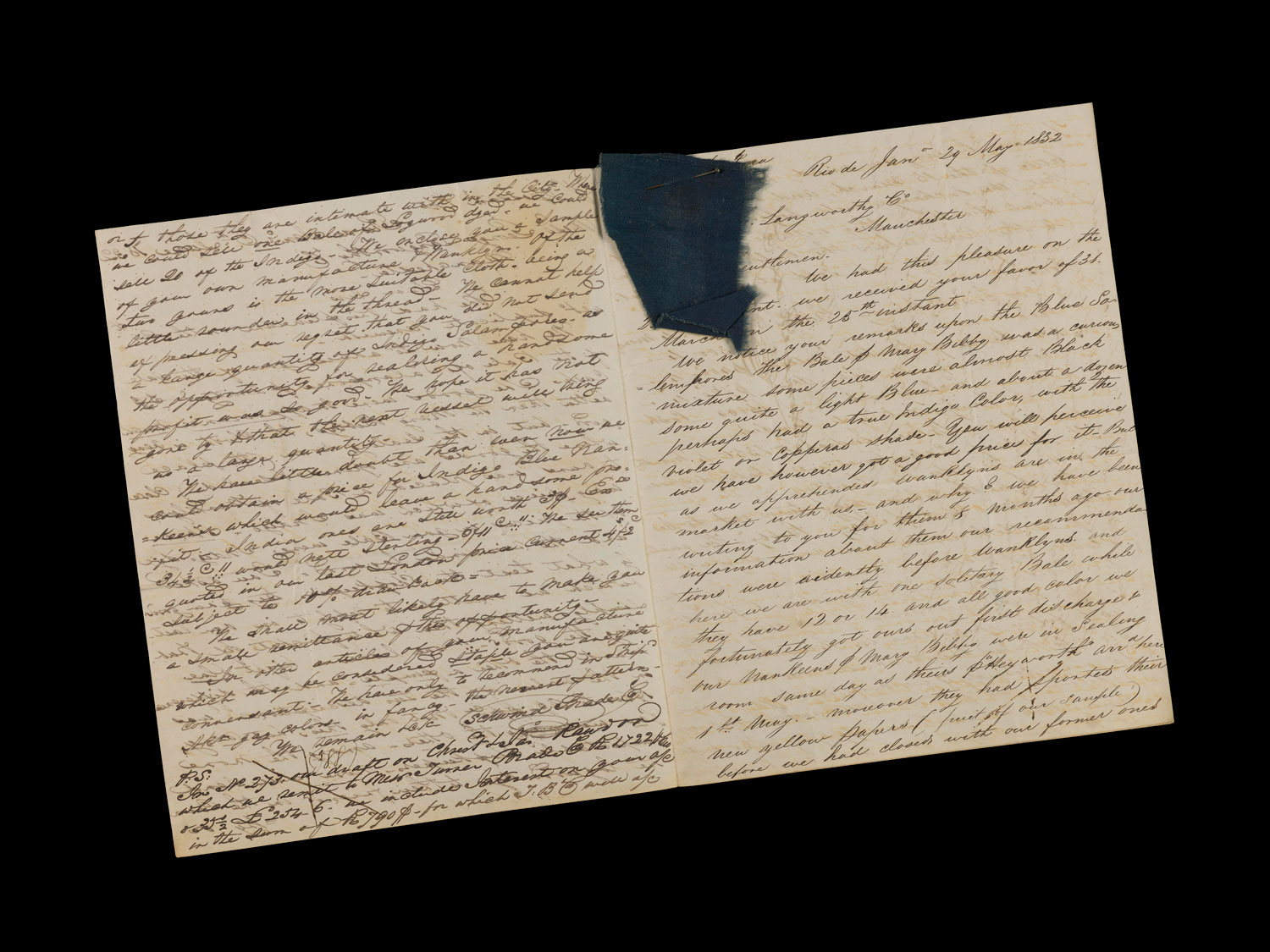

The correspondence between Langworthy and their agents stationed in Brazil also reveals a lot about the role merchanting played in placing Manchester’s cotton products at the centre of global trade. With such emphasis placed on Manchester’s manufacturing by historians, less attention has been paid to the important role of merchants. As Langworthy’s archive reveals, Manchester’s textiles did not simply sell themselves. The specific colour of products, their patterns and quality of material were all scrutinised by buyers. It wasn’t uncommon for consignments to be rejected outright or fail to obtain their expected price.

Textiles therefore required careful selection, design and marketing to ensure they appealed to overseas buyers. This is where the role of a trusted and competent overseas agent really came into its own. Overseas agents stationed in foreign ports were responsible for sending back messages to Manchester firms on the state of markets and advice on what products to send for sale. It was the strong knowledge of the consumer habits of the market administered to Langworthy by agents through letters carried on packet ships that allowed Langworthy to select and manufacture the right products.

Agents would observe which types of goods were selling well and obtain samples of them to send back to Manchester. The archive shows that samples were sent back to Manchester by post to illustrate the points that agents were trying to convey in the letters. The samples provided a visual aid that allowed Langworthy to accurately source identical textiles or adapt their manufacturing to imitate them.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Langworthy Brothers’ legacy is significant. Both Edward and George left £100,000 each to George’s son, a testament to the wealth they had acquired in their textiles business. Edward was an MP for Salford and the city’s Langworthy area is named after him.

Yet it is important to reflect on the fact that Langworthy’s accumulation of wealth from the profits of their textiles business would not have been possible without the labour of enslaved people who produced the raw cotton and formed a large part of the population in many of the locations where Langworthy sold their goods. As my research goes on, I am steadily uncovering the story of one of Manchester’s major textile businesses and revealing more of the complex, global story of Manchester’s role as Cottonopolis.

Find out more

Alexander’s research feeds into work happening across the museum to research and share more about Manchester’s textiles industry and its global histories, in particular those connected to colonialism and enslavement. You can also explore our Manchester, Cotton and Slavery Objects and Stories page and our Global Threads website, created in partnership with UCL’s Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.