Please note: Use Hearing Protection ended on 3 January 2022. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

On 15 June 1979, Joy Division’s debut album, Unknown Pleasures, was released. It was one of only two studio albums the legendary Manchester band produced, a legacy cut short by the death by suicide of lead singer Ian Curtis in 1980. The album was recorded at Strawberry Studios in Stockport and was produced by Martin Hannett, who gave it a unique electronic sound, very different from the punk aesthetic the band themselves aspired to.

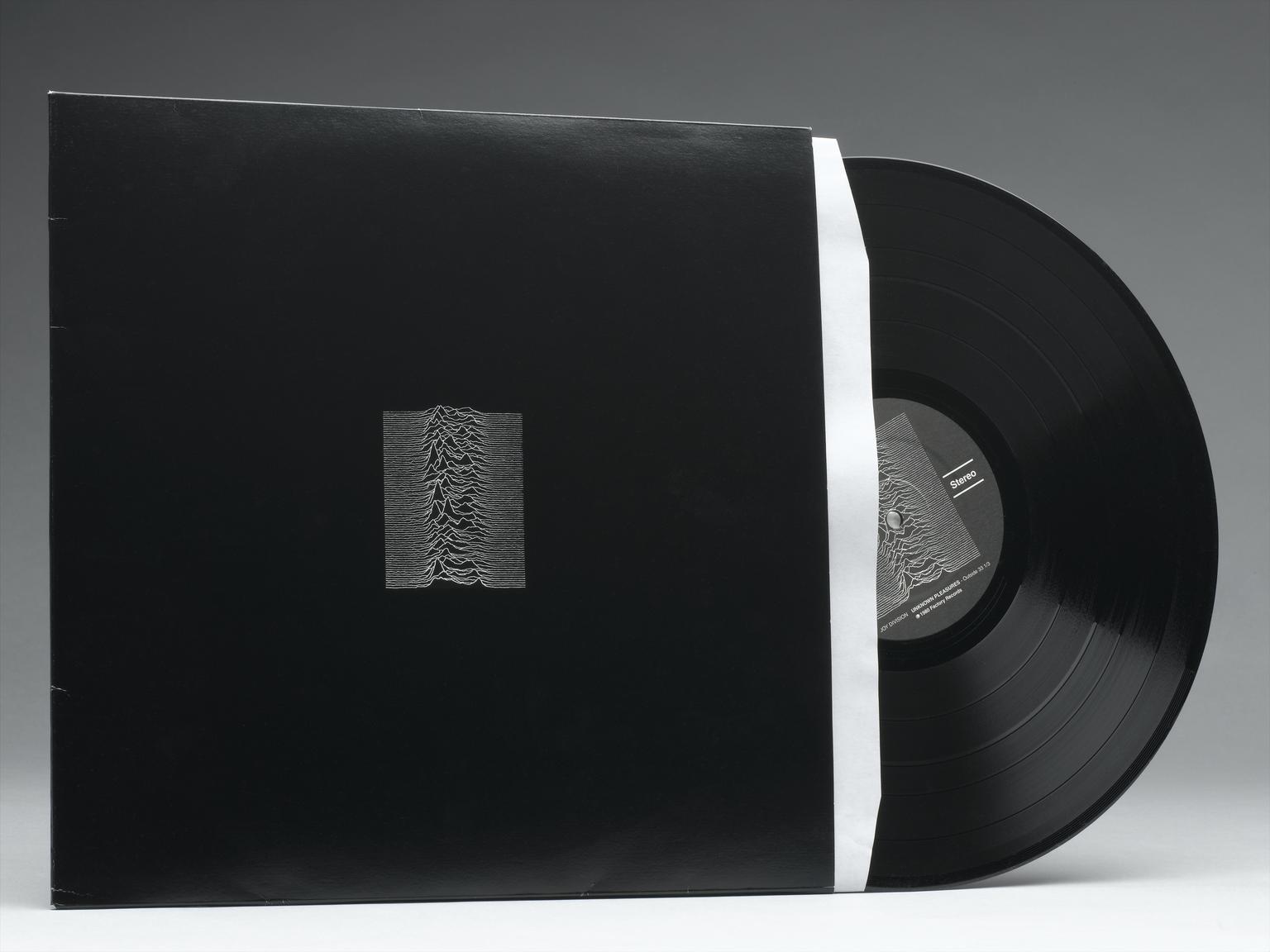

The record has gone on to be hugely influential and is frequently mentioned in best album lists, but almost as popular as the music is the artwork on the album cover. The small, white rectangle of wavy white lines set in the centre of a blank black background is instantly recognisable and has been reproduced thousands of times. But what exactly are those lines? How did they end up on an album cover only to be adapted and adopted for everything from t-shirts to homeware by companies and fans alike?

The image itself was found by Bernard Sumner, the band’s guitarist and keyboardist. He was working in Manchester city centre but spending a lot of his time in Central Library. That’s where he found a black on white diagram that struck him as a good design for an album cover. He passed it on to Peter Saville who was already known as Factory Records’ “in-house” designer. Saville made the image white on black, reduced the size and placed it in the middle of the black sleeve.

This illustrative image was indicative of the anti-establishment values of both Joy Division and Factory Records. As bassist Peter Hook says, having an image was much more ‘mysterious and enthralling than having your face stuck on the record cover’. They also didn’t copyright the image. One of the reasons the image is so popular and can be seen in so many places and forms is that it wasn’t owned by the band or Factory Records, and as Peter Hook again says, ‘what’s more punk than that?’

So, what was this enigmatic image that Bernard Sumner came across that day in Manchester Central Library? The lines are actually an infographic showing the radio waves made by a pulsar star and that’s where this story connects with another—the story of the pulsar’s discovery by Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

In 1967, Bell Burnell was a postgraduate student at Cambridge studying quasars using the Interplanetary Scintillation Array, a radio telescope. One day she noticed a regular spike in the read-outs occurring around every one and a third seconds. At first it was thought to be interference caused by humans, and it was even temporarily named “Little Green Man 1”, but she knew it was something else. After more of these pulses were discovered coming from different areas of space, it became apparent that they were a new type of star.

Now called CP1919, the diagram that Sumner found is of the pulses from that original star when it was observed by the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico by another PhD student, Harold D. Craft, Jr. The pulses are put in front of each other so they can be compared. As a star enters the final part of its life, it runs out of its nuclear fuel. Sometimes all that’s left is a very dense rotating object with a radius of only about 10 kilometres. These stars beam out radio waves that are detected when those beams pass our planet. Jocelyn Bell Burnell herself describes it as ‘being like a lighthouse’.

The discovery of pulsars won the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1974, but Bell Burnell was not named as one of the recipients. The omission was criticised at the time and has since become an infamous case of a female scientist not getting the credit she deserved. Bell Burnell herself is a little more philosophical about not being mentioned in the prize and you can listen to her talk about her experiences in the video below from Cambridge University. However, she’s very frank about the pressures of being a woman in science especially at that time, saying women were not expected to be anything other than wives and mothers. She says that she suffered from impostor syndrome and that’s partly what drove her. In 2018, she was awarded the prestigious Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics and she gave the £2.3 million prize money to help female, minority and refugee students to become physics researchers.

And, of course, her initial discovery has gone on to have a second life as an iconic album cover for a seminal Manchester band. Bell Burnell’s pulsar is now possibly the most recognisable scientific diagram in the world, seen on everything from mugs to tattoos, even if some people don’t know where it came from.