We spoke to our curators to find out about these incredible pieces of history.

The 250-year old invention that changed the world

Curator of Industrial Heritage Katie Belshaw says a seemingly unassuming object in the Textiles Gallery is one of the museum’s most precious objects:

“The water frame in the Museum of Science and Industry’s collection is a rather unassuming object. Made of wood and less than two-foot-tall, it is dwarfed by the imposing, iron-framed machines it shares its home with in the Textiles gallery, which thunder and clatter during daily demonstrations that bring the days of Cottonopolis to life.

“Yet although the water frame might not rival its neighbours in size or power, it is one of the Textiles gallery’s most precious objects. At almost 250 years old, the great-great grandparent of our working machines was a vision of the future when it was devised by Lancashire entrepreneur Richard Arkwright in the 1760s.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

“Since the first decades of the eighteenth century, makers had looked for ways to meet the ever-growing demand for cotton cloth. After years of tinkering, in 1767 a breakthrough came when Arkwright, working with a skilled clock-maker, John Kay, devised what became known as the water frame, a simple but remarkable spinning machine powered by a water wheel.

“Replacing the work done by human fingers, its four sets of moving rollers drew out the cotton fibres, before a spindle twisted the cotton into thread. Just one unskilled worker could supervise the machine. As long as they supplied it with cotton, replaced full bobbins with empty ones and pieced together broken threads, the water frame could spin more cotton more quickly than had ever been possible.

“By installing water frames in new, towering mills that had hundreds of workers toiling in time with the machines, Arkwright and his business partners created a new system of factory based, machine production. And although it was soon replaced by new innovations, the water frame was a spark of invention that helped trigger Britain’s industrial transformation.

“Thanks to the Heritage Lottery Fund the water frame will be on display here at the Museum of Science and Industry for years to come.”

The hidden network powering Manchester

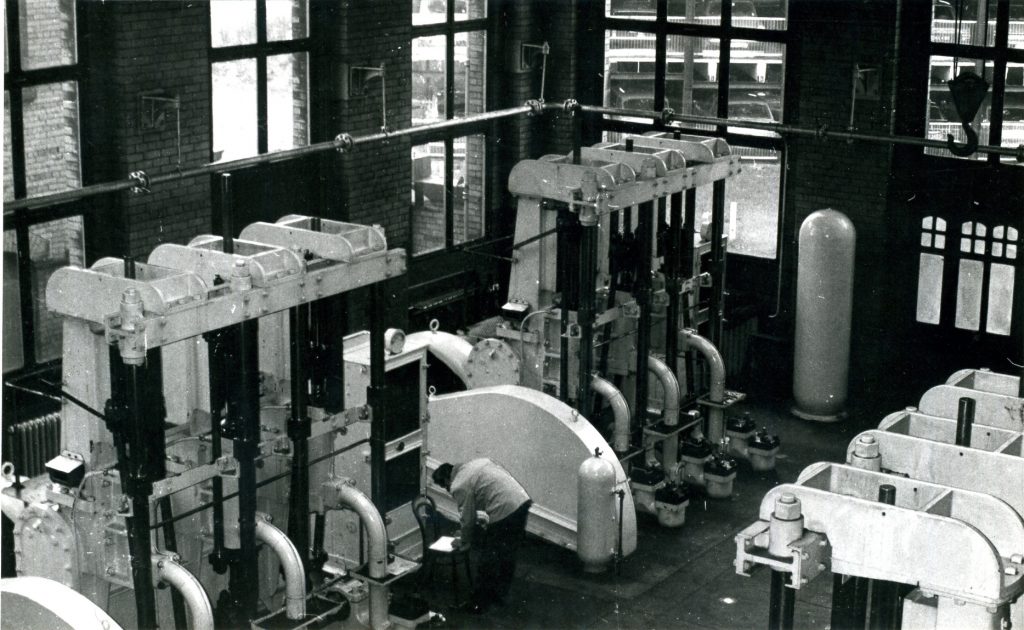

Associate Curator Sarah Baines says the hydraulic pumping engine made by W. J. Galloway & Sons, Manchester in 1909 was integral to Manchester’s success as an industrial city, but few know about the city’s Victorian hydraulic power network.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

“Clean, reliable, quiet water power. Sounds futuristic. Did you know that from 1894, water powered many of Manchester’s machines? Pumped to extremely high pressure at three stations around the city, it was distributed through a network of strong cast-iron pipes beneath the streets to where it was needed. It pushed people up in lifts, hoisted bales of cotton into warehouses, and powered machines in factories and workshops. It even wound up the heavy weights of the Town Hall clock, pumped the Cathedral organ and raised the safety curtain at the Opera House. Several other cities used hydraulic power, but Manchester’s system used a much higher pressure than the other systems.

“Manchester’s hydraulic power was most popular in the 1920s, when there were 600 consumers and more than 30 miles of pipework. Hydraulic power was especially useful where the need for power was intermittent rather than constant, for example passenger lifts, or warehouse machinery.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

“Originally a steam engine, our hydraulic pumping engine was converted to electric drive in 1927. It was one of six pumping engines installed at the new Water Street pumping station in 1909. The Water Street pumping station closed on Christmas Day 1972. It is the only surviving pumping station, and is now the People’s History Museum.

“Each of the three hydraulic power stations in Manchester had to pump their water up from a deep borehole because the water in the river and canals was too filthy and polluted to use in the high-pressure hydraulic system. The clean water was stored in tanks on the roof. Anecdotally, the power station engineers kept the roof-top tank stocked with fish, and used it as a swimming pool on hot summer days.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

“From 1974 the pumping engine was on public display at the University of Salford, but its future was not secure. It found a permanent home in the Power Hall at the Museum of Science and Industry in 2002. Thanks to an HLF grant, the Museum of Science and Industry were able to arrange for the pumping engine to be carefully dismantled from its previous location, professionally restored so that it could be demonstrated, and then re-erected in the Power Hall, where it is now demonstrated as part of the museum’s daily working machinery demonstrations.

“Thanks to the HLF funding received in 2002, visitors today can see the only remaining pumping engine from a Manchester’s little-known Victorian hydraulic power network.”