Our city has a reputation for lots of things, not least its wet weather. Technically, Manchester isn’t even close to being the UK’s rainiest city, coming in below Leeds, Bradford, Glasgow and Cardiff, amongst others. Nevertheless, in the wake of Storm Christoph, as Manchester emerges from yet another bout of torrential rain and flooding, and as scientists predict that climate change will lead to more extreme rainfall, now feels like a good time to reflect on our city’s relationship, past and present, with the wet stuff. I’ve taken a dive into the collections and stories here at the Science and Industry Museum to see what they can reveal about Manchester’s rainy reputation.

If you ask someone what they think of when they hear ‘Manchester’, they will probably say ‘rain’. They might also mention the cotton industry, upon which Manchester’s 19th-century rise to fame (or infamy) was built.

There is a popular anecdote that says Manchester’s success with cotton was all down to its damp weather, since it provided the ideal humidity for cotton’s processing. There is definitely some science in this. In a dry atmosphere, cotton fibres lose their moisture to the air, which makes them brittle and more likely to snap. Get the humidity right and the fibres keep their moisture and stay strong and stretchy, which makes for good quality yarn that is less likely to break. It’s why modern cotton mills invest in fancy humidification systems to keep the atmosphere just right.

© Science Museum Group Collection

I’m not convinced the naturally damp climate was the be all and end all for the success of Manchester’s textiles industry. Even in the early 19th century, factory owners were taking artificial measures to keep cotton mill atmospheres humid, putting trays of water underneath looms and even injecting steam from the mill engine’s boiler onto the factory floor, creating highly unpleasant conditions for workers in the process.

Nevertheless, we can certainly credit the abundance of rain with creating the fast-flowing rivers that powered machines like Arkwright’s water frame in Lancashire’s earliest cotton mills, and for providing the water needed when steam engines took over the job of driving the machinery. Manchester’s dyeing and bleaching industries also needed huge amounts of water. They also made an awful habit of releasing their wastewater back into the city’s rivers, causing them to flow red, green and even purple.

© Science Museum Group Collection

Speaking of water and polluting industries, it was following studies of mid-19th-century Manchester’s rainfall that Scottish chemist Robert Angus Smith first coined the phrase ‘acid rain’. He was one of the first scientists to make the connection between industrial pollution and the acidity of urban rainfall, noticing that it damaged trees, corroded ironwork and weathered the sandstone facades of Manchester’s buildings. He published his findings in 1872 in Air and Rain: The Beginnings of a Chemical Climatology, although it wasn’t until almost 100 years later that the true extent of acid rain’s global impact was understood, with the term becoming a household name.

Actually, Robert Angus Smith wasn’t the only scientist to study Manchester’s rainfall in the 19th century. As well as transforming our understanding of chemistry and colour blindness, John Dalton was a keen weather watcher, keeping a daily record of his meteorological observations for over 50 years, including rainfall. Amongst his scientific instruments and research notes, the museum’s collection even includes John Dalton’s umbrella, which certainly looks like it saw a fair bit of rain in its time.

© Science Museum Group Collection

© Science Museum Group Collection

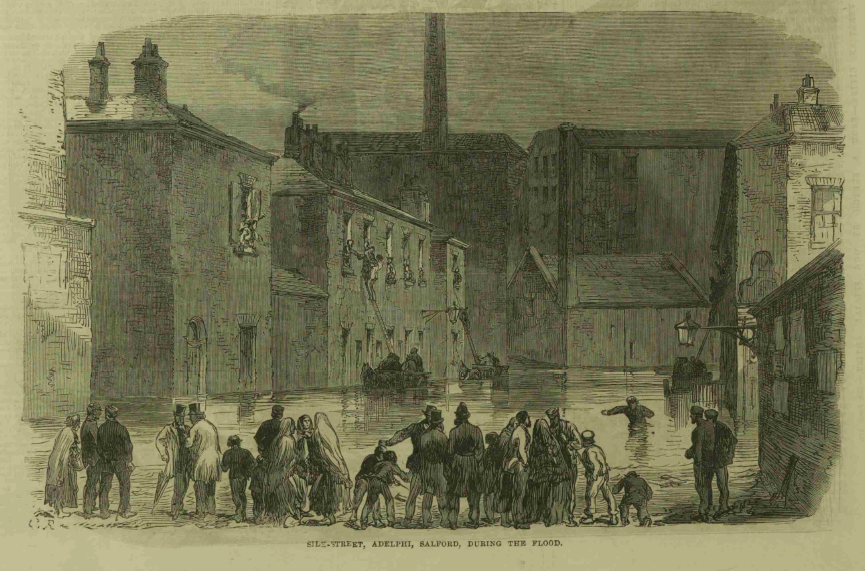

Manchester’s rapid 19th century urbanisation coincided with a marked increase in the impact of heavy rain on the town. As the town grew, sections of Manchester’s rivers were covered, narrowed and straightened to make way for new buildings and roads, affecting their natural flow. Water pollution caused obstructions and reduced the capacity of the rivers. The paving of land without adequate drainage systems left rainwater with nowhere to go. Severe flooding hit Manchester and neighbouring Salford in 1852, 1866 and 1872, highlighting the need for better town planning, reduced river pollution and improved drainage.

Image courtesy of Illustrated London News/Mary Evans Picture Library.

Apart from an umbrella, as any self-respecting Mancunian knows, the rain mac is another must-have accessory for surviving life in the rainy city. With both a thriving textiles industry and its fair share of inclement weather, Manchester has been at the forefront of the development of waterproof fabrics.

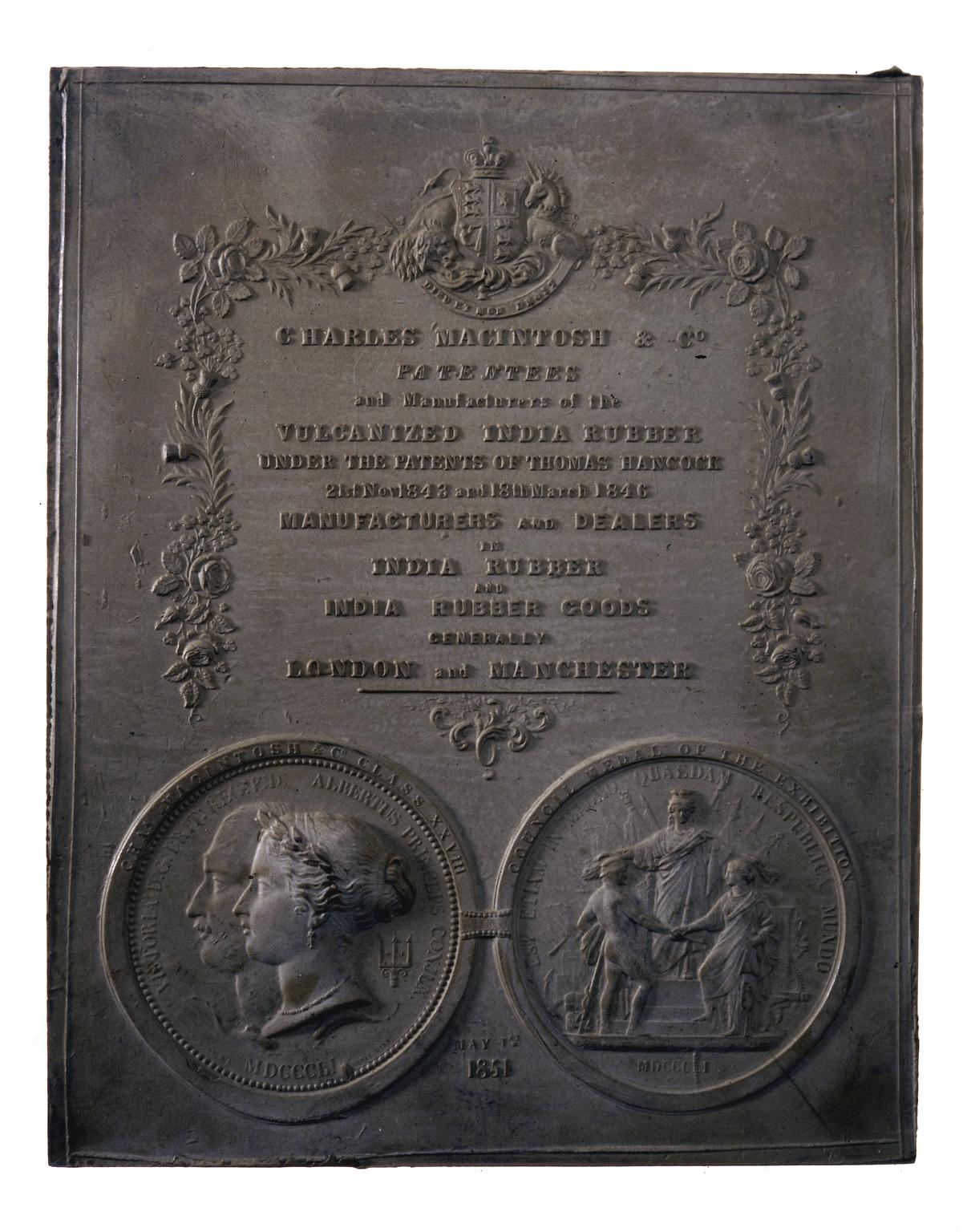

In 1823, Glasgow-based scientist, Charles Macintosh, patented a new type of waterproof material by sandwiching softened rubber between two pieces of textile. Soon after, he went into partnership with Manchester cotton manufacturers the Birley brothers, and together they began producing their rubberised fabric, and the soon to be famous mackintosh coat, from their mill on Cambridge Street. By all accounts, the earliest macs were heavy, smelled terrible and lacked breathability, which caused the wearer to sweat profusely, somewhat defeating the object of their use. However, a new process called vulcanisation pioneered by the company in the 1840s dramatically improved the quality of their rubberised fabric and transformed demand for the mackintosh.

© Science Museum Group Collection

Thereafter, many other companies set up in Manchester alongside Macintosh and Co. manufacturing waterproof goods. Today Manchester is still home to outer-wear suppliers including Regatta, Henri Lloyd and Private White V.C., who have been manufacturing raincoats from the same mill since 1853.

From cotton to chemistry, rain is a striking theme in Manchester’s history, having helped influence some of the industrial developments and scientific breakthroughs that have put the city on the map and shaped our world. Yet, as it was for the inhabitants of rapidly industrialising 19th-century Manchester, the risk of flooding from heavy rain continues to threaten the city’s population and its economy.

The Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, which has a research base at the University of Manchester, predicts that climate change will lead to more frequent and severe weather events, including flooding. As our earth’s atmosphere warms up, it will be able to hold more moisture, which in turn will lead to more intense periods of rainfall. Manchester is already experiencing increasingly frequent flooding, and this looks set to continue. It’s just one more reason why the world needs to act now to curb the burning of fossil fuels and reduce carbon emissions.

If you’re interested in finding out more about climate change, visit the Manchester Science Festival page, where you can watch a number of insightful talks all about the topic and ideas for a better world.

2 comments on “Manchester: Our rainy city”

Comments are closed.

This is just fascinating, I am a newly appointed heritage researcher for Salford Archaeology, and recent census delving into Ancoats during the second half of the nineteenth century has revealed the occupation of umbrella maker in quite a few households….e-mail if you would like me to condense this research?……

Katie, your description of industrial waste being pumped into Manchester rivers reminds me of the Irwell in the 1970’s. I worked in a telephone exchange on the Salford bank of the Irwell just along from Blackfriars Bridge. The few windows we had looked out over the river, which at times did show all the colours of the rainbow. At low water levels you could also see a GPO vintage equipment rack protruding from the mud.

Excellent article, really enjoyed it.

Tim Banks, SIM Volunteer