Please note: Electricity: The spark of life ended in April 2019. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

In our upcoming exhibition Electricity: The spark of life, we celebrate the 110th anniversary of the Manchester Electrical Exhibition held at Platt Fields. Rusholme and Victoria Park archive have loaned us a set of souvenir postcards produced for the event. These sit alongside contemporary newspaper reports from the Manchester Guardian and a minute book from Manchester Corporation’s Parks and Cemeteries Committee, on loan to us from Manchester Archives and Local Studies.

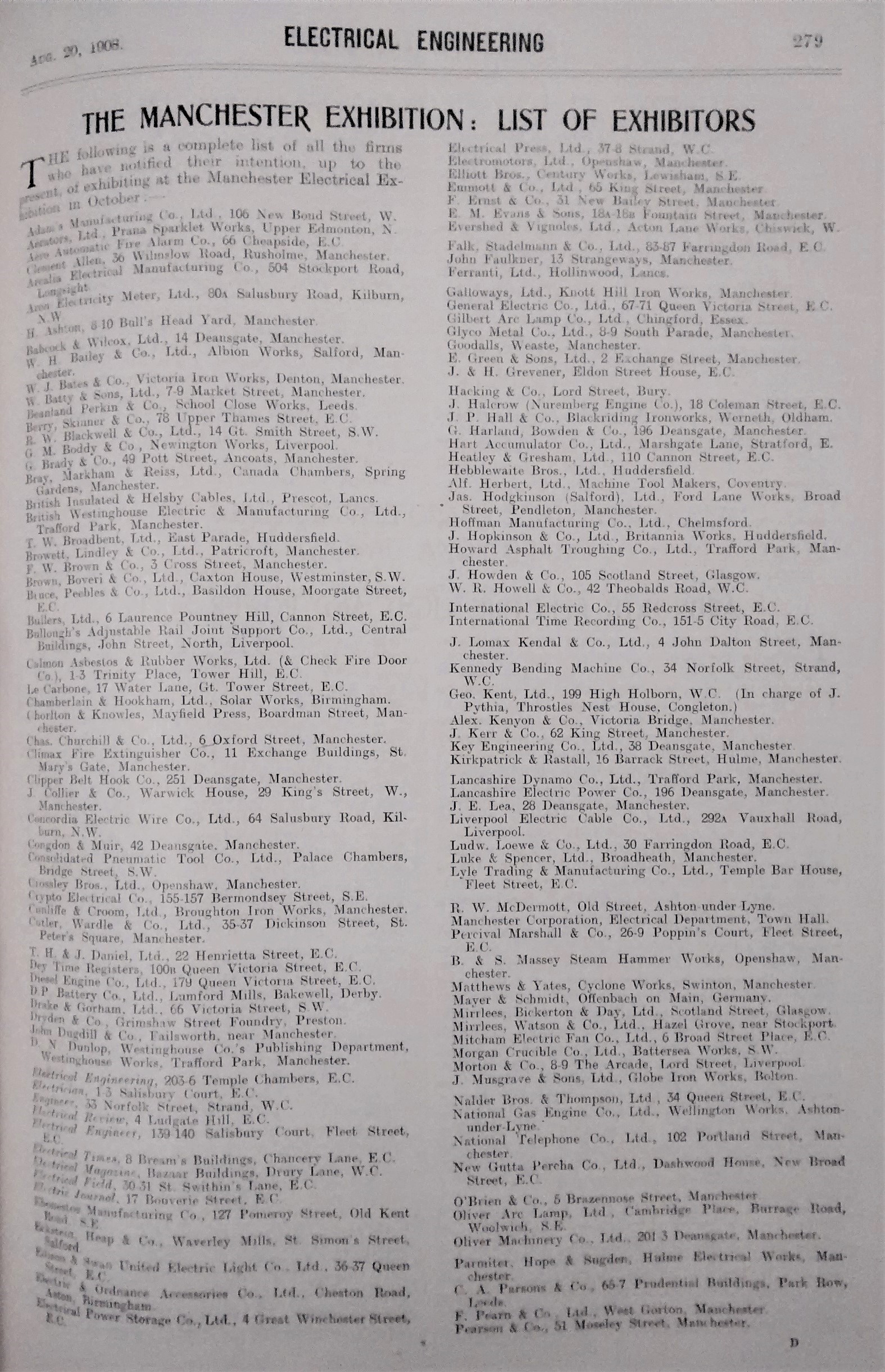

In 1908, the National Electrical Manufacturers’ Association (NEMA) delivered a month-long exhibition of electrical engineering technology in Manchester. NEMA had chosen the location on the basis that Manchester was known as the centre of the greatest industrial area in the world, home to companies like Ferranti, British Westinghouse, Crossley Brothers and Mather & Platt. Examples of innovative electrical engineering from the region’s manufacturers were displayed in abundance at the exhibition.

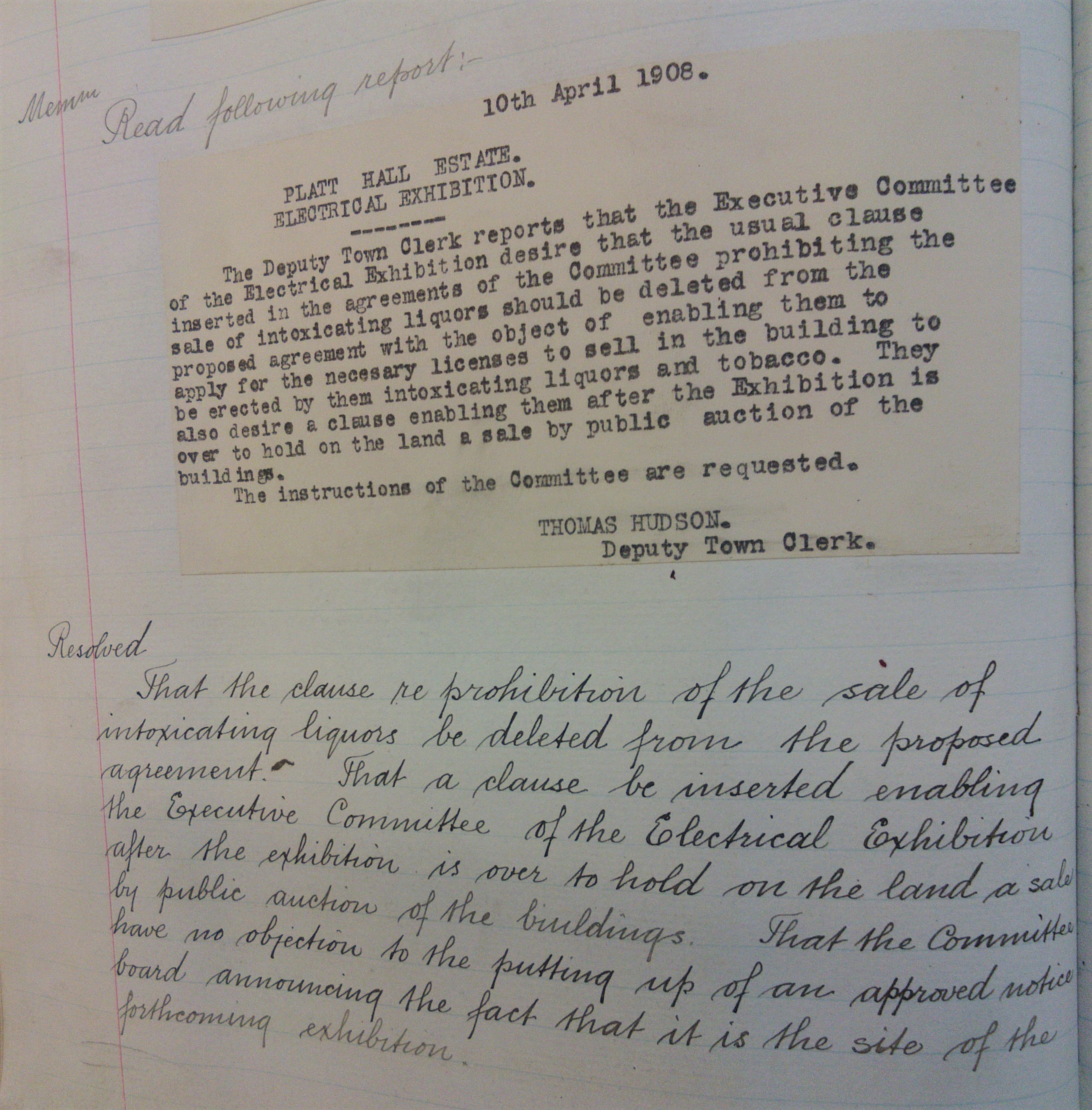

The minutes of Manchester Corporation’s Parks and Cemeteries Committee reveal how the exhibition came to be held at Platt Fields. The council had only recently bought the Platt Hall estate for the benefit of residents in Rusholme, seeing an opportunity to provide unemployed labourers with work through its redevelopment into a public park.

The exhibition was originally planned to be held at Belle Vue Pleasure Gardens in East Manchester. However, the NEMA committee saw the potential in the Platt Hall estate after the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Show was held there. NEMA approached the council about holding their exhibition in the same location, using the same exhibition structures. Manchester Corporation was reluctant at first and NEMA had to submit a revised proposal in February 1908, agreeing to build a new structure for the exhibition that could be dismantled at the end of the event.

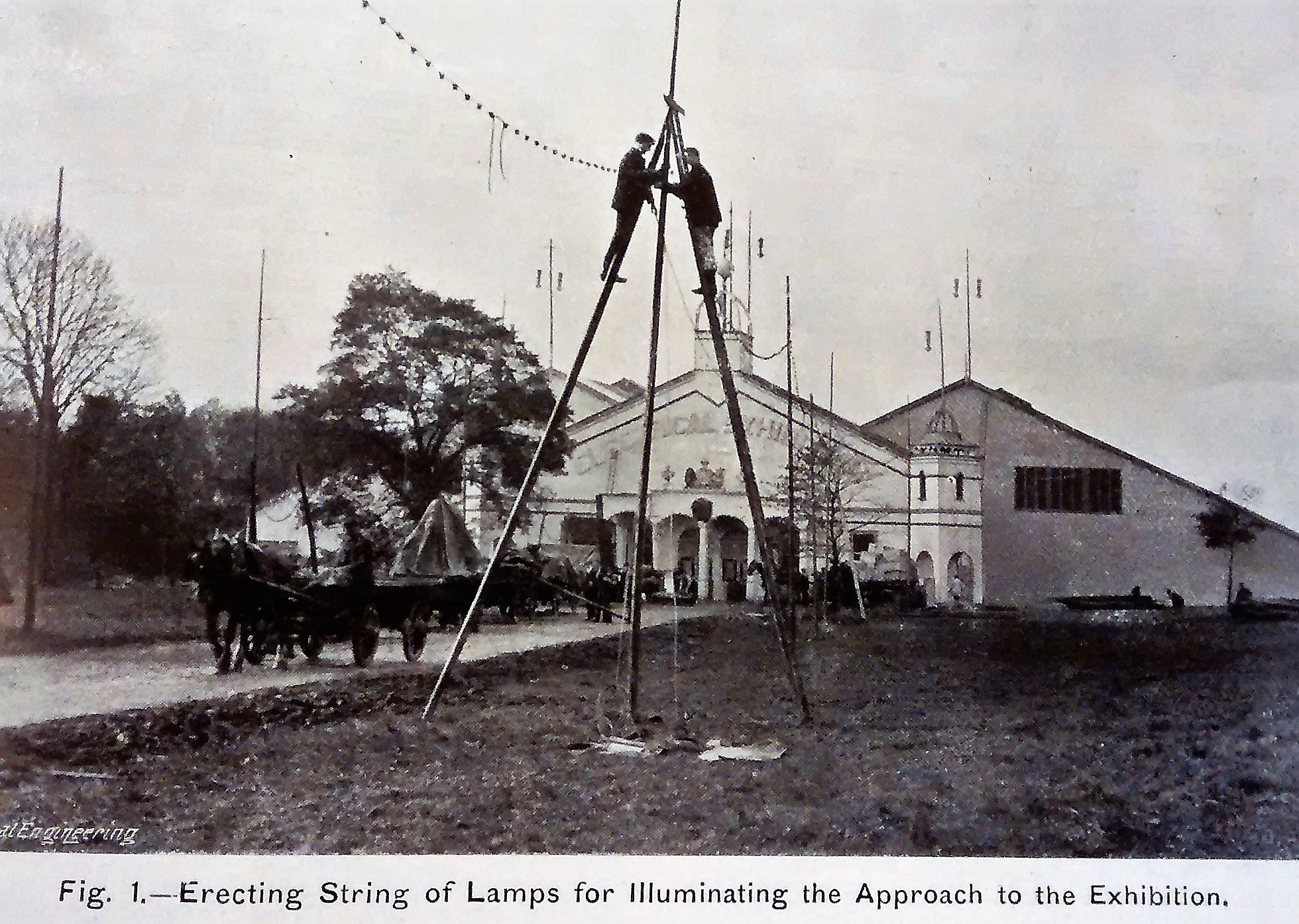

Eventually the council provided the site free of charge and even offered an AC electricity supply from its Stuart Street power station at a reasonable rate. The wooden exhibition hall was designed so that daylight was excluded from the interior, allowing artificial electric lighting to be showcased to its best advantage. As well as its own sub-station supplied with electric current from the Stuart Street power station, the site also had a DC backup system that consisted of a Crossley engine coupled to a Mather & Platt dynamo.

This electricity supply powered an external circuit of arc lights for the exhibition, producing dazzlingly bright lighting.

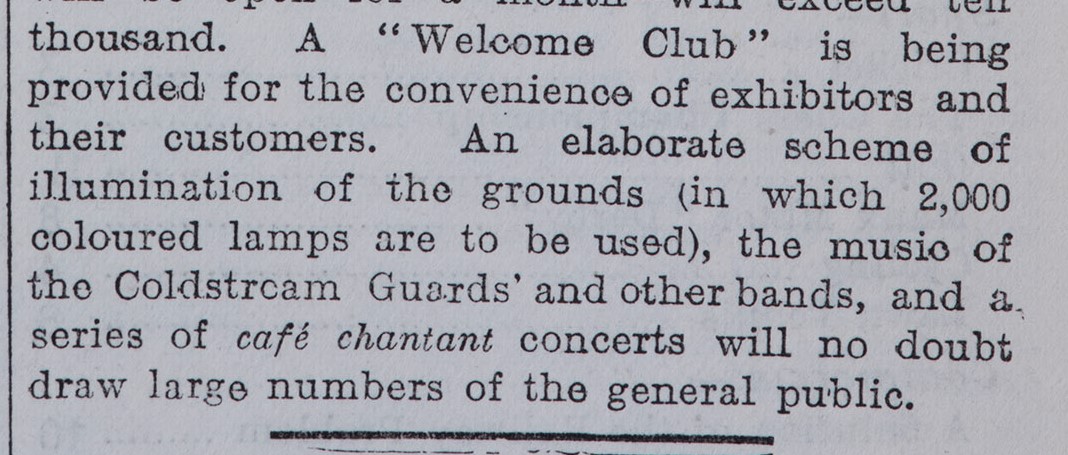

The Manchester Guardian‘s report on preparations for the exhibition makes it clear that the event wasn’t just about presenting the latest in electrical innovation to interested engineers and businessmen. The report mentions music performed by the Coldstream Guards and other bands among other entertainments.

Mancunians enjoy a spectacle. You’ve only to wander across town when it’s Chinese New Year, Manchester Day or Pride to know that. In 1908, this love for the spectacular clearly included bright, multicoloured lights and the band of the Coldstream Guards.

Fortunately for visitors to the exhibition who wanted to relax among the lights and the music, an entry in the minutes of the Parks and Cemeteries Committee from April 1908 reveals that the council had agreed to a particular request from the exhibition organisers. They asked for a clause in the official agreement that prohibited the sale of intoxicating liquor and tobacco on the site to be removed.

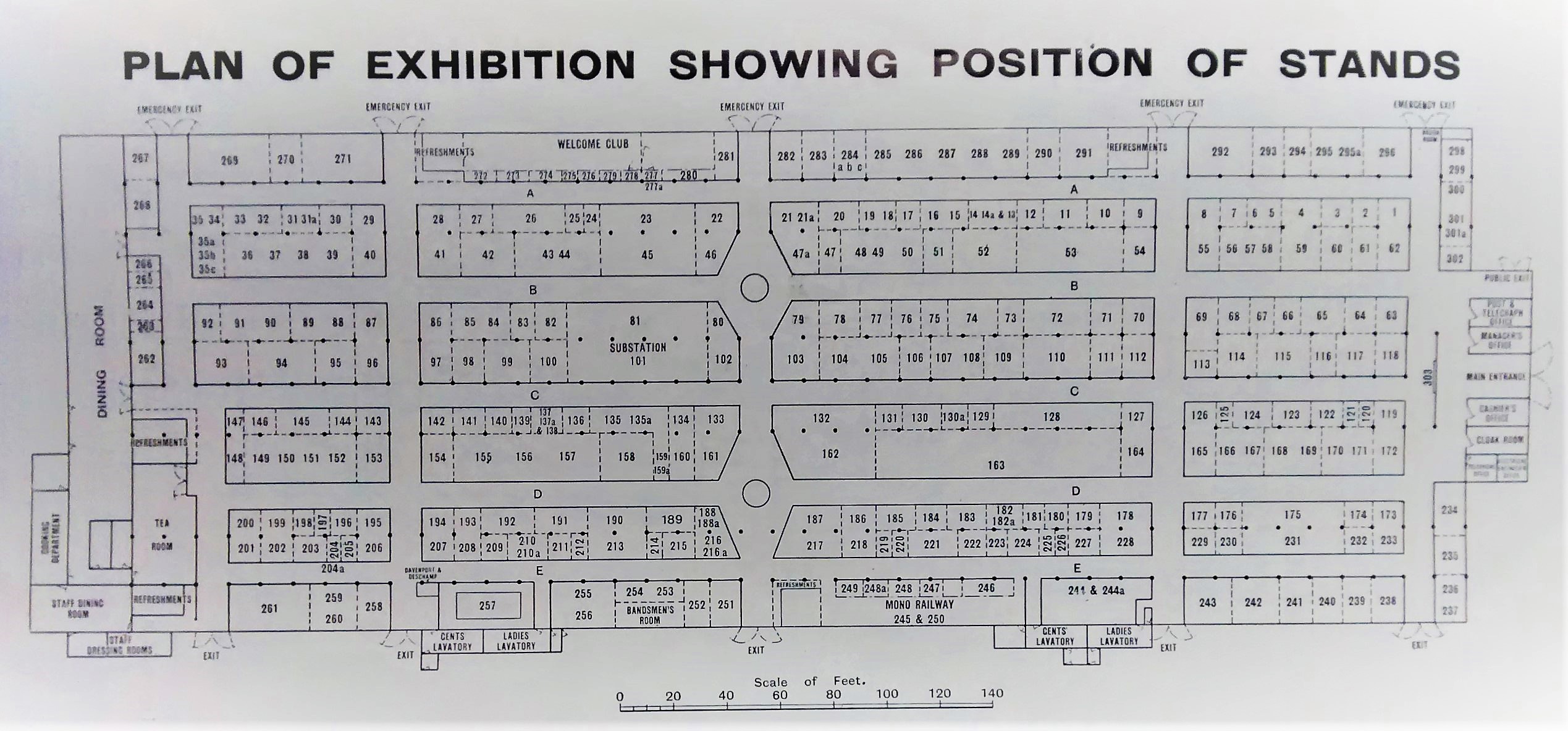

Music and drinking aside, the Manchester Electricity Exhibition was home to over 250 stands showcasing the latest developments in electrical engineering, from generators, transformers and switch gear, to incandescent lightbulbs and a model electrical home.

Over the month of October 1908, 300,000 people visited the exhibition, which is over five times the capacity of the Etihad stadium or four times the capacity of Old Trafford football ground.

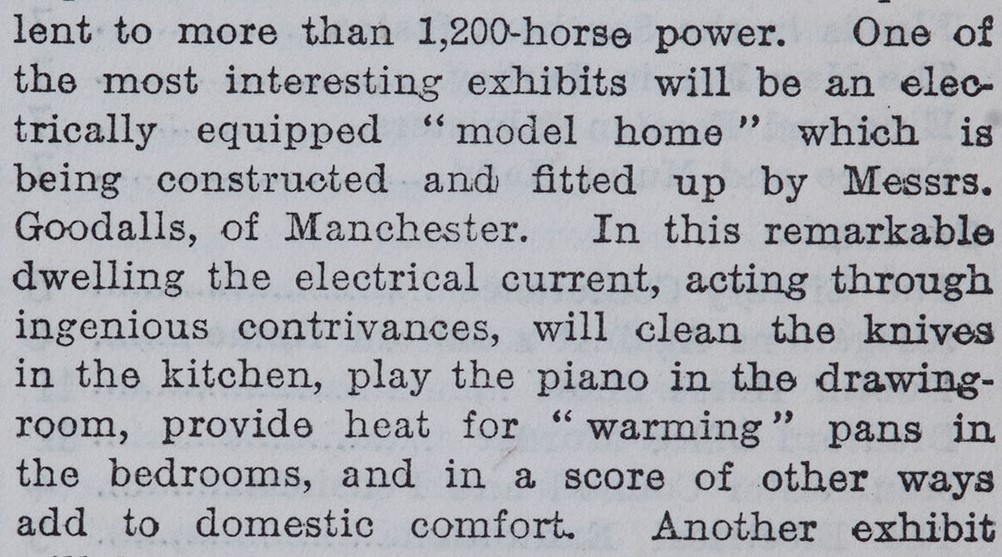

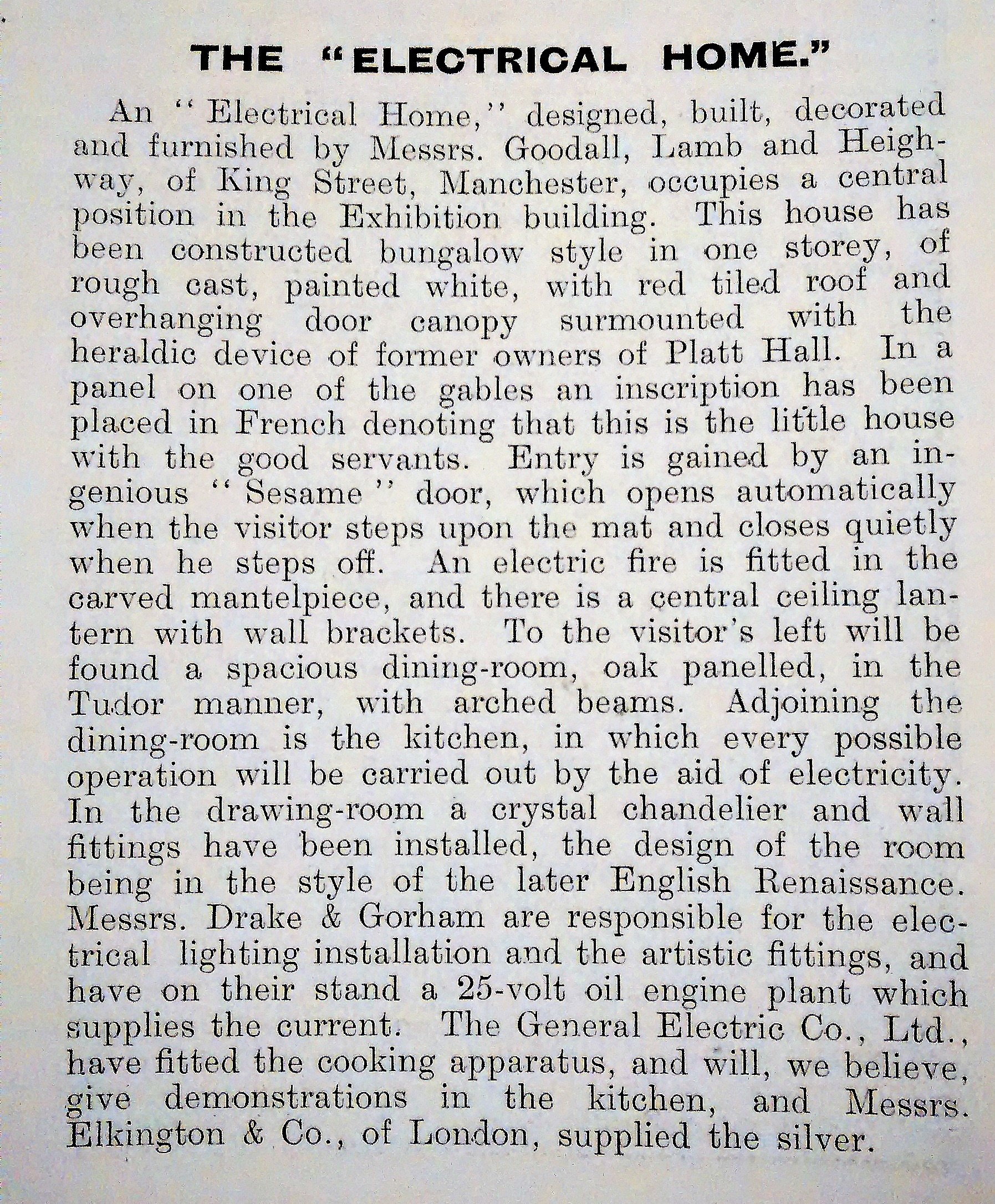

In August 1908, before the exhibition was even open to the public, the Manchester Guardian enthused about what promised to be its star exhibit, the electrically equipped model home built and fitted out by Goodall, Lamb and Heighway Ltd of King Street, Manchester, referred to as Messrs Goodalls in the article.

Goodalls, as craftsman furniture makers and not electrical engineers, were undoubtedly making use of an opportunity to promote their furniture against a backdrop of modern convenience.

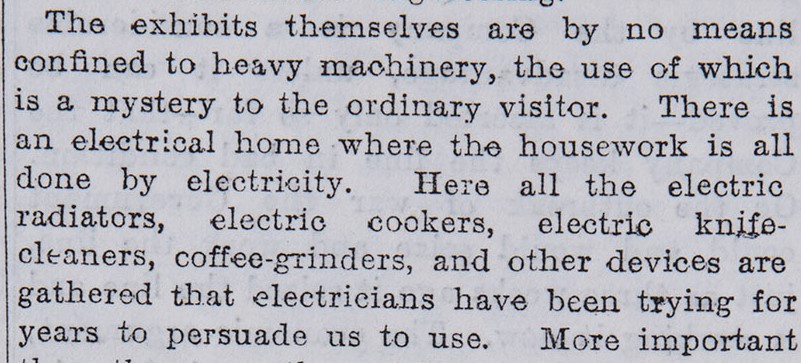

A couple of days before the official opening of the exhibition, the Manchester Guardian ramped up the excitement, reporting on the types of household gadgets and appliances that would appeal to the more general visitor, including electric knife-cleaners and coffee grinders.

We all have at least one friend who is the first to get their hands on the newest technology, willing to believe the innovators that product X will change their life. While the latest must-have gadgets of the Edwardian era were different in form to the gadgets 21st century early adopters pledge for on Kickstarter, they shared an important characteristic—their reliance on electricity.

The Manchester Guardian‘s reporter also made frequent reference to an item that surprised me, because I’ve only ever seen it appear in saloon-bar scenes in films—the electrically powered, self-playing piano. It had never crossed my mind that someone might want such a thing in their own home. While the Edwardians loved the sound of tinkling ivories in the parlour, they perhaps didn’t love it so much that they wanted to make the effort to perform themselves. What could be more perfect than an electrically powered, self-playing piano, in that case? The model home featured two—the Electrelle manufactured by J J Hopkinson Ltd and the Harper Electric Piano made by the Harper Piano Co Ltd.

Once the exhibition was open to the public, the Electrical Engineer joined the Manchester Guardian in its excitement about the model electrical home, describing in detail the almost magical automatic door into the building, as well as the architecture and furnishing of the house.

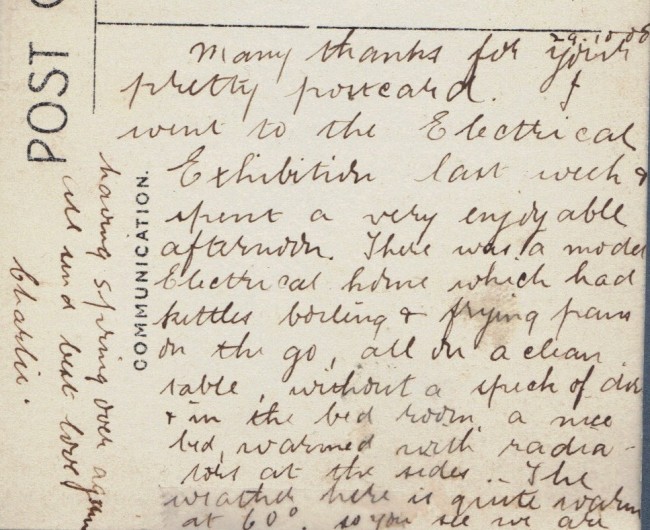

The model electrical home turned out to be just the curiosity for visitors to the exhibition that the Manchester Guardian predicted. Writing on the back of a souvenir postcard purchased at the exhibition, one visitor described the experience for the benefit of people at home:

“I went to the Electrical Exhibition last week & spent a very enjoyable afternoon. There was a model electrical home which had kettles boiling & frying pans on the go, all on a clean table, without a speck of dust & in the bedroom, a nice bed, warmed with radiators at the side.”

As you’ll see when you visit Electricity: The spark of life, events like the Manchester Electrical Exhibition and its model electrical home were tools used by manufacturers of electrical machinery and domestic appliances to reduce customer resistance to electricity and spark curiosity about its potential.

The model electrical home at the Manchester exhibition is the earliest that I’ve found reference to in the UK. Between 1908 and 1935, model electrical homes became increasingly sophisticated as electricity became the must-have energy source for the modern home.

2 comments on “Sparks of desire: The Manchester Electrical Exhibition”

Comments are closed.

I have some old electric light fittings which my father kept. They are some sort of plated metal and are quite ornate. I am loathe to throw them out. Would you be interested in having them? And, if not, do you know of anybody who might be interested? Many thanks.

Hello David. Sorry for the delay in getting back to you. You’ll find information on how to contact us with objects that you’d like us to consider for our collections on our website here.