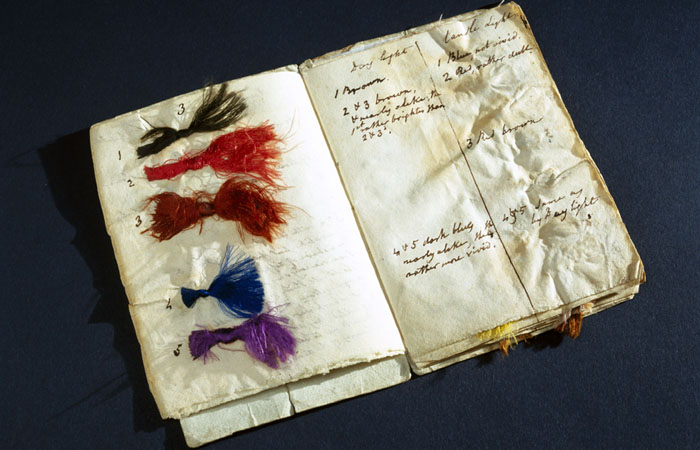

‘Blue, not vivid’, wrote the chemist John Dalton in 1798-99, to describe the knot of silk thread glued into the top of this notebook. In daylight it appeared brown, and by candlelight, blue. A forest green is how I might describe it, or a dirty green. The notebook, from the collections of the Science Museum Archives, is over 200 years old, so the colour of the threads may have changed since Dalton’s time, but to me it is definitely green. You can judge for yourself when it is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry on 25 October 2016 for the Manchester Science Festival.

It is 250 years today since John Dalton was born in the village of Eaglesfield in Cumbria (6 September 1766). By the time he was 26, and living in Manchester, he had begun to realise that he saw colour differently to other people. He gave his first account of his colour vision to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1794, and it is the first description of colour blindness, a condition that took his name – Daltonism.

Dalton was a meticulous observer. But for me, what is most interesting about Dalton’s study of his colour vision is the way he used everyday objects as reference points: to describe colours in a common language, and to compare his perception to that of others. Those everyday objects are very much of Dalton’s time, so they give a personal insight into 18th century Manchester.

‘Green woollen cloth, such as is used to cover tables appears to me a dull, dark, brownish red colour. A mixture of two parts mud and one red would come near it. It resembles a red soil just turned up by the plough’.

– John Dalton

In another comparison, he wrote, ‘The face of a laurel-leaf (Prunus laurocerasus) is a good match to a stick of red sealing-wax’. The image below is how it would have looked to Dalton, using a piece of red sealing wax thought to have belonged to Dalton (from the collections of the Museum of Science and Industry) and viewed with a photographic filter.

We now know that Dalton had red-green colour blindness, or deuteranopia. This was discovered in 1995, when DNA analysis revealed that he lacked the gene for the receptor sensitive to medium wavelength (green) light. Dalton had speculated that the jelly-like part of his eye, the vitreous humour, was tinted blue, acting as a filter, so he asked that his eyes be examined after death. On 28 July 1844, the day after he died, local doctor Joseph Ransome performed the autopsy. ‘Perfectly colourless’ was the result. The eyes were retained by the Literary and Philosophical Society, of which Dalton had been President for nearly thirty years, and donated to the Museum of Science and Industry in 1997. The results of the DNA analysis of a tiny fragment of this tissue were published in the journal Science.

There are many celebrations of Dalton’s anniversary this year, such as this exhibit at the Science Museum and events at the University of Manchester. Our event for Manchester Science Festival will showcase our collections, and some of the ways colour vision has been tested since Dalton’s days. There will be sheep’s eye dissection demonstrations, to see that jelly-like vitreous humour, and the part of the eye that was sampled for the DNA analysis. Plus, there will be games and simulations that explain why being colour blind has its advantages in the animal kingdom. We’ll also run a book on the colour of that green thread, and post our results on the blog here in November. I’m sure you can do better than ‘dirty green’.

Top and middle image credit: Science Museum/Science and Society Picture Library

Bottom image credit: The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London