Please note: Electricity: The spark of life ended in April 2019. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

First, pretend to lift up the delicate object. Carefully manoeuvre your fingers and arms to accommodate its fragile form.

Then, proudly hold it out at arm’s length. Present its grandeur to the world. Finally, smile a big toothy grin and smash it to the floor!

Or at least that’s how you do it if you’re nine years old and your school pals are watching.

They answered correctly, straight away.

my name is Adam flint, and I am the creative content developer at the science and industry museum

Working with our talented Explainer team, I create shows, workshops and learning resources for young people. These draw out the fun, relevant and accessible parts of the subjects in our galleries so that our visitors can explore them and build their own learning.

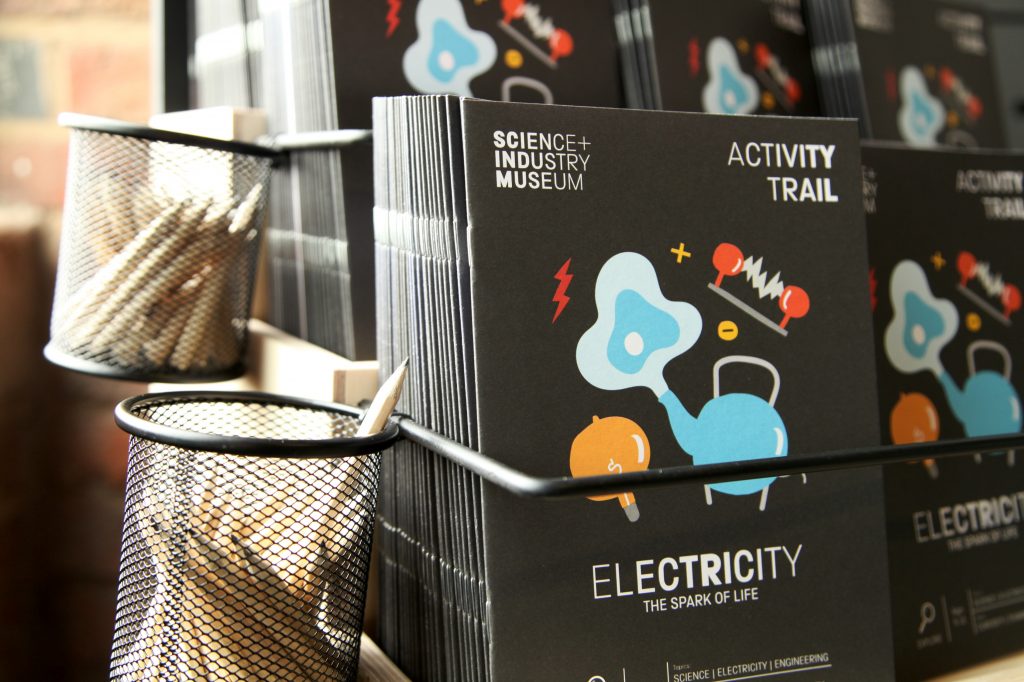

Most recently I’ve been working on the activity trail for Electricity: the spark of life

Families can sometimes find it difficult to engage with our objects, especially the older, less recognisable ones, like those in Electricity: The spark of life.

We know from the success of last year’s Robots activity trail that a resource like this can help a group to hop over these boundaries and make personal connections.

The most important (and fun) part of developing trails is to test our ideas with young visitors.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

The results are always fascinating

When we tested the ideas for the new booklet with children, we knew that the anarchy with the (pretend) glass lampshade was a clear sign of success.

Forget the lack of respect for the preservation of valuable historical objects (sorry Curators!) This demonstrated everything we wanted to see:

- A personalised, relatable response to an object on display

- A fun, social experience, inspired by our collection

- And a visitor looking closer, engaging with the details of the object

Not only did this boy recognise the materials and properties of the object, but there was an understanding that this was an item that had prestige—it might have displayed status, demanding respect. So, what’s the best way to convey this to your friends while playing the game?

Undermine that and smash it!

This group of boys then scattered, engaging with other objects on display, searching for another that they could connect to and convey physically in a way that their friends would understand. Another boy demonstrated a model of atomic structure—all jagged points and converging lines—by dropping some Peter Crouch-style robot dance moves.

I had no idea what he was doing, but his friend guessed instantly.

At nine years old, these boys didn’t grasp what the object represented, but they now knew its name and will probably remember it in future.

Other students were observed asking their colleagues and teachers about different objects: ‘what is it?’, ‘how did it work?’ and ‘who used it?’

They pulled out archive drawers and read interpretation text. One girl told her teacher that ‘this looks like something we have at home’.

Teachers took pictures of the students posing as old electric kettles. The hum of activity brought the gallery to life, with other visitors seen smiling at their efforts. This activity was a success and the user testing proved that.

When user testing an activity for the trail, we ask three questions

- Does the activity prompt visitors to look closer at objects?

- Does the activity inspire an individual connection or response to objects?

- Does the activity lead to social interaction with the rest of a group, inspired by objects?

If the answer is yes, they became options for the final product.

If the answer is no, it’s clear. Very clear. There is no finer critic than unfiltered five to 11 year olds!

One activity that we tested challenged visitors to choose an object and create a sales pitch, selling its virtues to their group. Our little coffee-and-Hobnobs-fuelled writers’ room (members of the Learning, Collections and Exhibition teams) were particularly excited about this one.

The children had a different view

‘What’s a sales pitch?’…’why would you even buy an old thing?’…’Boring.’

I asked one girl what she thought of the activity. She yawned at me, patting her open mouth with her palm. Brutal and concise, but at least we knew that the activity didn’t work.

New exhibitions at the Museum are developed to be as accessible and open as they can be

Careful attention is paid to the use of language, the tone of voice and the physicality of galleries.

However, museums can still be scary. They can be overwhelming. They can feel authoritative, as if this isn’t a place for everyone. Visitors can feel a pressure to leave with new knowledge that they must retain and recite. This impacts a person’s confidence when approaching an exhibition.

Our activity trails aim to work with the exhibitions and counteract this, especially for families and groups who’ve chosen us as their place to visit in their valuable free time. Trails aim to pull out different learning outcomes alongside knowledge: inspiration, enjoyment, and perhaps a shift in attitude and a new sense of curiosity.

The answers to the three questions above point to identifiable signs of success.

If the answers are yes, then we could also be seeing positive behaviours. We might even spot science skills or historical investigation skills: observation, information retrieval/processing, communication, forming questions and inferring.

Often, visitors already have these skills. They just don’t realise it or recognise when they’re demonstrating them.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

The boy from the earlier story sums this up

He observed the glass lamp shade.

He considered the details and made an inference.

He synthesised what he’d concluded and communicated this to his friends in its most simple and understandable form: he pretended to smash it, giggled, and then ran off to find something new.

One comment on “Trialling trails: Adding family fun to our exhibitions”

Comments are closed.

Very nice initiative by the whole team. All the best and keep it up.