When Manchester commemorated this significant anniversary, our curator of Industrial Heritage, Katie Belshaw, caught up with Shirin Hirsch, researcher at the People’s History Museum, to explore some of the Peterloo objects in the Science and Industry Museum’s collection and find out what they can tell us about the day’s events and their impact:

I’m a big fan of clocks and the Science Museum Group’s collection isn’t short of interesting examples (check out this intriguing mill clock or this amazing railway timepiece if you don’t believe me).

But one that has always fascinated me is a longcase clock made between around 1820 and 1830, with an extremely detailed, hand-painted decorative dial. It’s a fantastic example of craftsmanship, but what makes it even more special, unique in fact, is that it depicts a scene from the Peterloo Massacre, which took place over 200 years ago in Manchester, on 16 August 1819.

Science Museum Group Collection

Science Museum Group Collection

The name painted in the middle of the dial links the clock to the Stancliffe family, who were well-known clock makers in Halifax from the early 18th century. Painted iron clock dials like these were an innovation of the 1770s, thanks to the increasing availability of good quality, rolled iron. They offered the potential for illustration in colour, which boosted the decorative clock industry. Commemorative clocks became big business, usually marking events such as naval battles.

We don’t know who this clock was made for, but purchasing such a fine, and probably made-to-order example certainly wouldn’t have been cheap, and the clock would likely have been a statement of its owner’s political stance and their place in society.

I asked Shirin to explain what the scene painted on the clock tells us about what happened on the day of the Peterloo Massacre:

“You get a sense more than anything else of the chaos of the day. In the background you can see the mass of people. This was an immense but peaceful gathering, and there are estimates of 60,000 protestors there in St Peter’s Field on the day of the massacre. These were people from across Lancashire who had marched with their families to demand political representation and the right to vote.

“The protestors were met with the violence of the British government when the Manchester and Salford yeomanry were ordered by magistrates to break up the demonstration. You can see this in the painting, the yeomanry on horseback with their sabres attacking the protestors.”

The violence that day resulted in the death of at least 18 people and the injury of 700 more. They were protesting peacefully with banners and flags, for rights that in Britain we now take for granted.

Shirin explained that in the aftermath of the massacre, the government cracked down on the movement for political reform:

“The government brought in the Six Acts which suppressed the reformers. Many of the movement’s leadership were imprisoned. Henry Hunt, the main speaker at Peterloo, was sentenced to two and a half years in prison. Anyone who spoke out against the government was at risk too.”

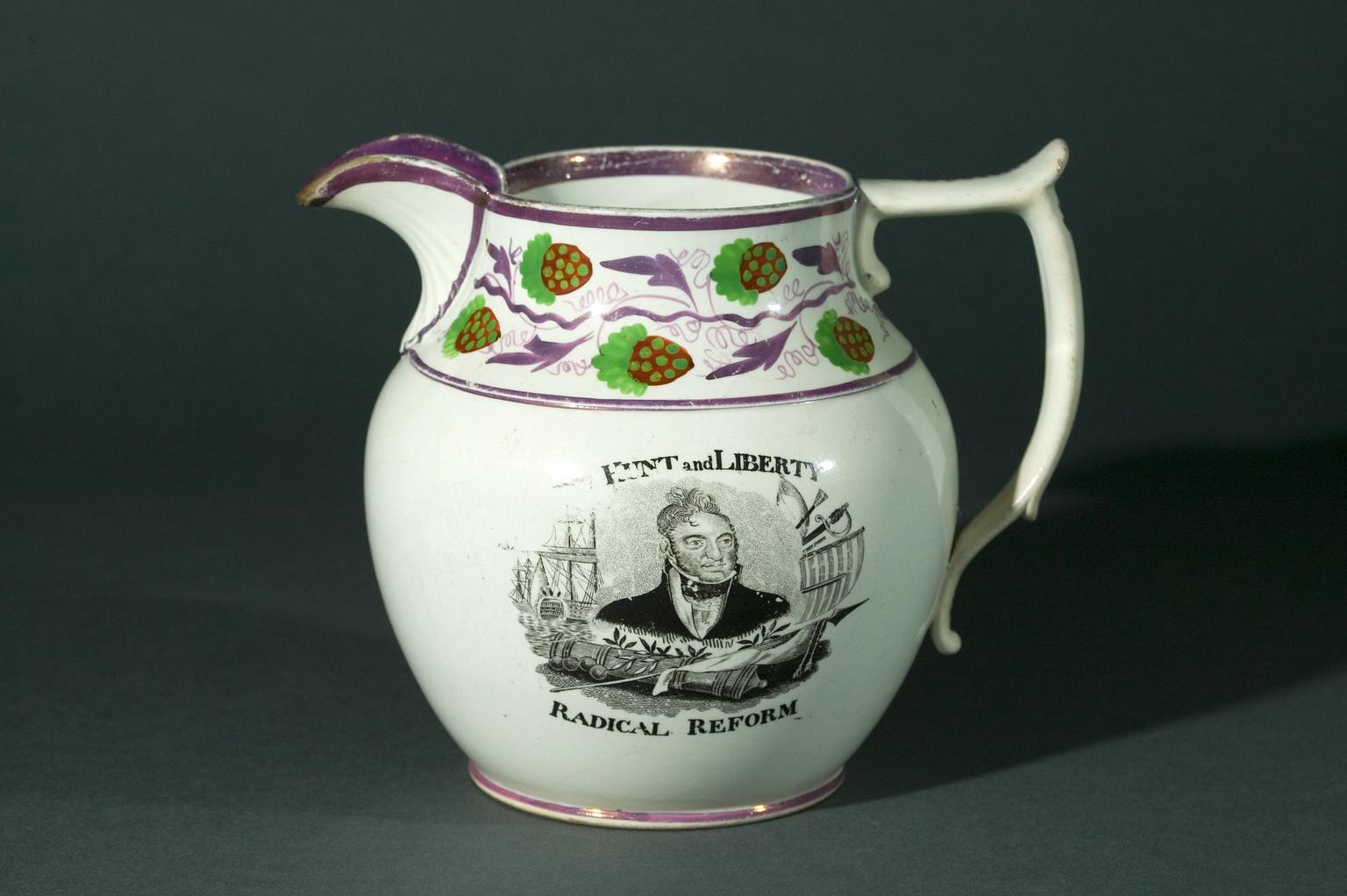

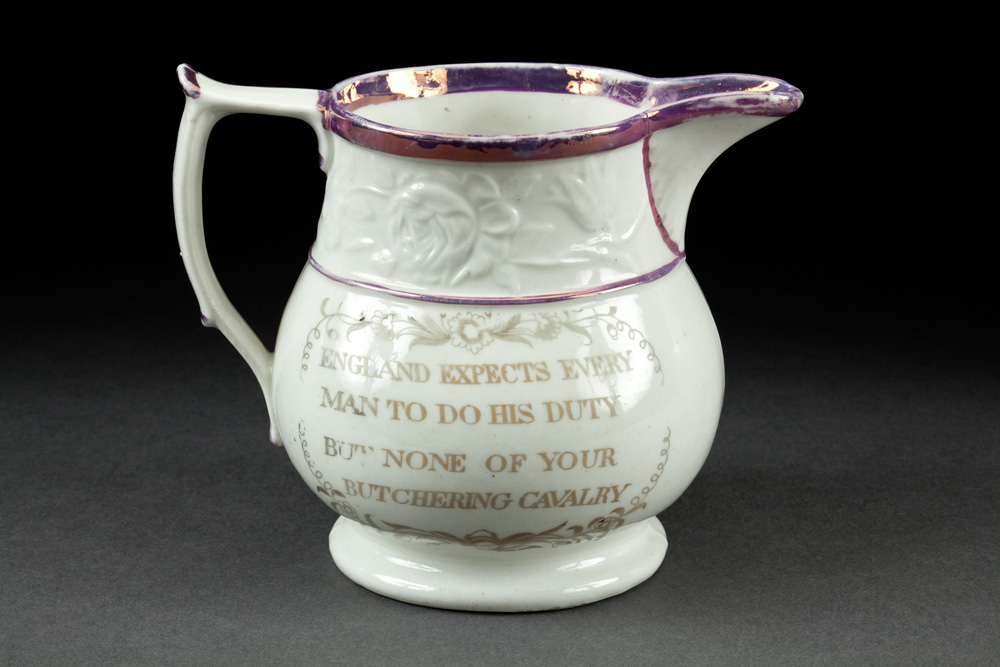

Yet attempts to cover up the massacre did not stop the production of thousands of Peterloo-themed commemorative souvenirs. Pottery makers raced to create transfer-printed tableware like these jugs, which are part of the museum’s collection.

Science Museum Group Collection

The jugs show the face of Henry Hunt and denounce the government violence. Commemorative ceramics like this were already commonly produced for events like royal or sporting events, but until Peterloo, had never been created for a political cause.

Items like the jugs, as well as countless handkerchiefs and printed caricatures, songs and poems, acted as cultural protests. They reached a wide audience, helping to ensure the Peterloo Massacre was remembered and uniting people in the cause for political reform.

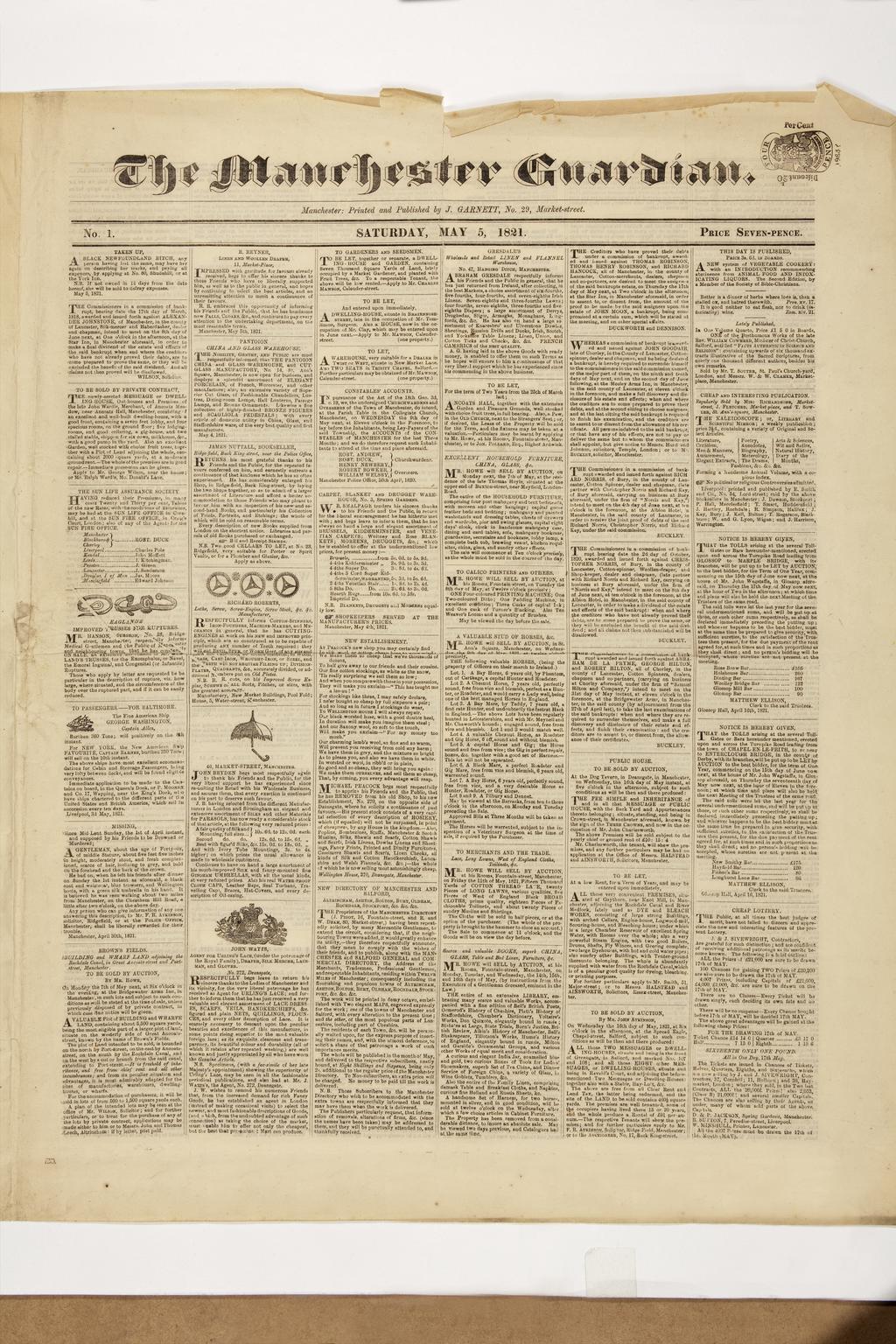

Also created with the intention of spreading the word about political reform was the Manchester Guardian newspaper, which was set up in 1821, two years after the Peterloo Massacre. Manchester cotton merchant John Edward Taylor founded the newspaper. He had witnessed the Peterloo Massacre and government attempts to cover up the violence.

Taylor wanted a newspaper that would truthfully report on the campaign for political reform. The newspaper became the Guardian in 1959 and is now read by around one million people a day. A copy of the front page is now in the collections.

Science Museum Group Collection

Peterloo has an important legacy. It exposed the deeply rooted corruption of the government and started a long process of political change and democratisation of the vote in Britain. It cemented Manchester as a cradle for political protest, where an increasingly politicised working class found its voice, working conditions influenced socialist thinkers Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, and the Pankhurst family led the fight for women’s suffrage.

It is also a great example of how a political incident can galvanise the public through publicity and commemoration. So, as we look back on the events of over 200 years ago, whether it’s a Boris Johnson gif or a Jeremy Corbyn t-shirt, Peterloo is still very much with us.