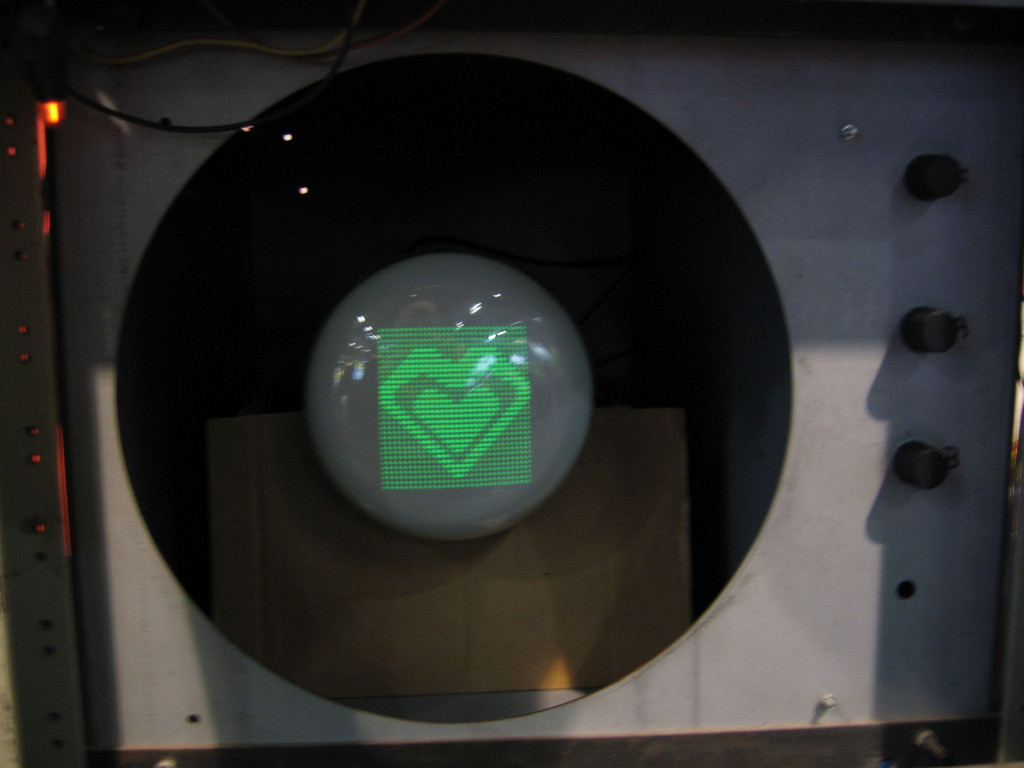

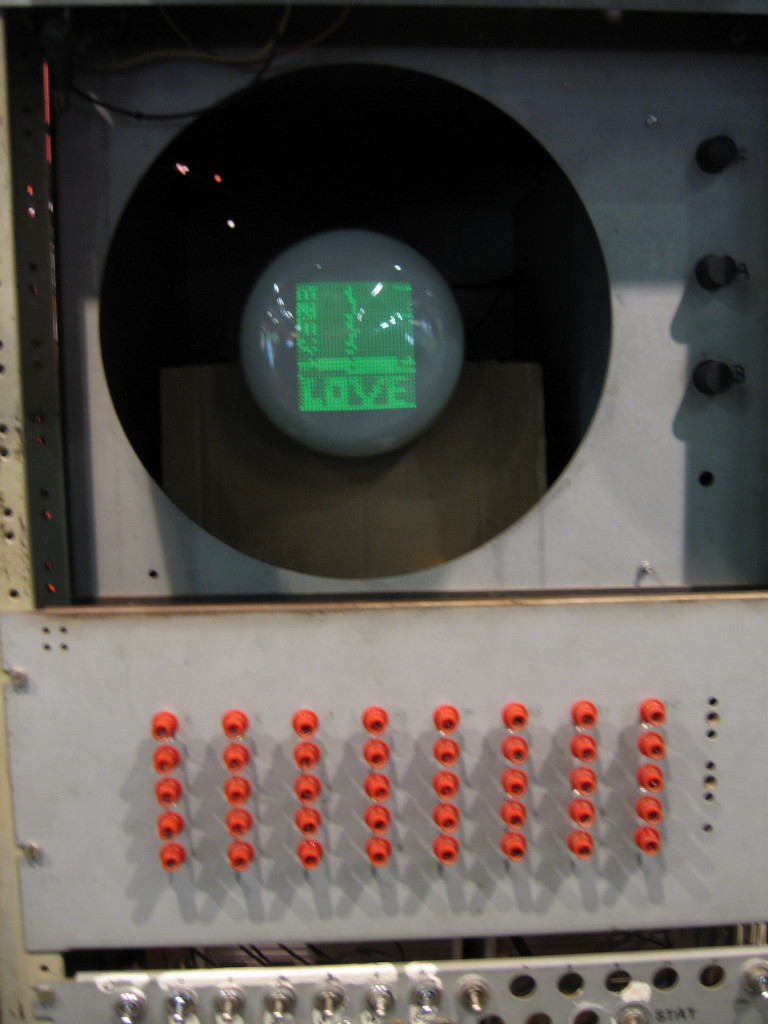

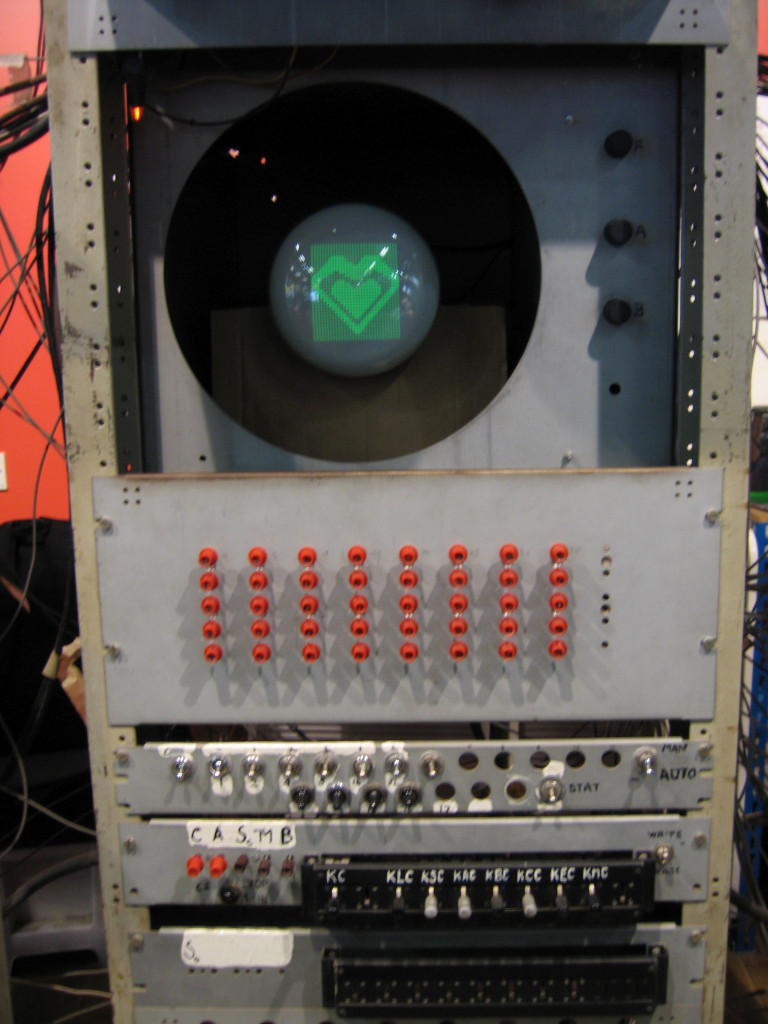

In August 1953, one of the first ever software developers, Christopher Strachey, showed his romantic side when he wrote an algorithm designed to automatically generate love letters.

He wrote his playful program for the world’s first commercial computer, the Ferranti Mark I, at the University of Manchester. He fed words like ‘beloved’, ‘darling’, ‘lovingly’ and ‘desire’ into the program, which were then randomly put into a letter template. The letters were always mysteriously signed ‘MUC’, which in fact stood for Manchester University Computer.

The program is considered the first ever example of digital art.

|

|

Strachey pinned his computer-generated love letters on the notice board of Manchester University’s Computer Department to the great puzzlement and amusement of his colleagues. They were gobsmacked when he explained that he had instructed the machine to generate them.

It’s strange and uncanny that randomly generated letters made up from a limited pool of ‘romantic’ words can have an emotional effect on us. This was all part of Strachey’s demonstration. He intended for the program to generate letters that would elicit feelings and emotions, fully aware that the letters were produced by ‘a rather simple trick’ and that the computer was ‘not really “thinking” at all’[i]:

DARLING SWEETHEART

YOU ARE MY AVID FELLOW FEELING. MY AFFECTION CURIOUSLY CLINGS TO YOUR PASSIONATE WISH. MY LIKING YEARNS FOR YOUR HEART. YOU ARE MY WISTFUL SYMPATHY: MY TENDER LIKING.

YOURS BEAUTIFULLY

M.U.C.

HONEY DEAR

MY SYMPATHETIC AFFECTION BEAUTIFULLY ATTRACTS YOUR AFFECTIONATE ENTHUSIASM. YOU ARE MY LOVING ADORATION: MY BREATHLESS ADORATION. MY FELLOW FEELING BREATHLESSLY HOPES FOR YOUR DEAR EAGERNESS. MY LOVESICK ADORATION CHERISHES YOUR AVID ARDOUR.

YOURS WISTFULLY

M.U.C.

It is no surprise that Professor Strachey was interested in the philosophical implications of computing. Strachey knew Alan Turing from his time at King’s College, and Turing had moved to Manchester ahead of Strachey. When Strachey arrived in 1951, Turing ‘decided to drop him in at the deep end, and suggested he try writing a program to make the machine simulate itself’. Once Strachey left the room, Turing joked with a colleague, ‘That will keep him busy!’[ii]

Strachey first wrote a program to make the machine produce music – it played the national anthem and Baa Baa Black Sheep, recorded by the BBC at the time. Soon after the love letter demonstration, Strachey went on to create the world’s first computer game: draughts for the Pilot Model ACE in Spring 1951, playing the first ever game in Manchester. Copeland observes that ‘The idea of the thinking machine, an electronic brain, was in the air at Manchester’.[iii]

To find out more about the early days of computing and its connection to Manchester, visit our Objects and Stories page, where you will also find out about the Baby computer – the world’s first stored program computer and the machine that closely preceded the romantically minded Manchester University Computer.

Sources:

[i] Strachey, C. S. ‘The Thinking Machine’, Encounter, vol 3 (1954), pp. 25-31 (p.26).

[ii] Copeland, Jack. Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age, Oxford: OUP, 2012, p. 166.

[iii] Copeland, Jack. Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age, Oxford: OUP, 2012, p. 167.

Image credits:

All images provided by the Computer Volunteers at the museum.

2 comments on “Can you code love?”

Comments are closed.