If you’ve caught one of our Explainers’ Rocket talks you may have heard how the rise of trains and the railway network helped footie fans travel for away games. With another exciting season over (and a certain Manchester team victorious once again) plus two British teams about to battle it out in the Champions League – one from the North and one from the South – we asked Dr. Alexander Jackson, Collections Officer at the National Football Museum, about how railways have influenced the popularity of football and how big games brought Northern fans ‘down South’ for the first time:

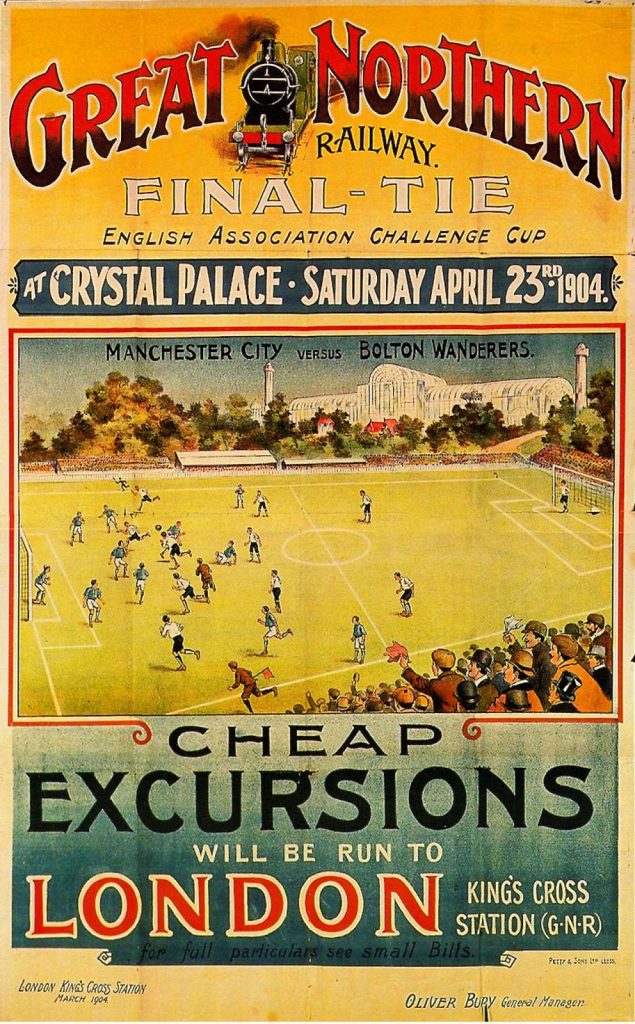

In 1904 Manchester City reached their first FA Cup final. Some 100 special trains brought some 40,000 northern fans to join some 20,000 from across London and the south of England at the Crystal Palace ground where they saw City beat Bolton Wanderers 1-0.

Such a crowd for a football game was unheard of when the FA Cup was first played for in 1872. Then only 2,000 spectators watched The Wanderers, an amateur team made up ex-public schoolboys, defeat officers from the Royal Engineers. By the early 1880s, working-men from Lancashire were beginning to challenge the supremacy of the public school boys, backed by travelling fans. In 1882 the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway provided special trains to take 2,000 fans to the FA cup semi-final in Huddersfield and 1,200 to London for the final, the first ‘northern invasion.’ The following year Blackburn Olympic, cheered by fans wearing their best Sunday clogs, became the first northern team to win the FA Cup. A few years later professionalism in the game was legalised and by 1906 the formally elitist game had become, in the words of historian Tony Collins ‘a commercial juggernaut that commanded the attention of millions.’

Underpinning this growth were the railways and other forms of transport allowing the new working-class fans to travel to games all over the country and home again in one day. Reactions to these travelling fans were mixed though. In his match report on that first Manchester City cup final for Athletic News (published just across the road from the National Football Museum at Withy Grove), England’s leading sportswriter James Catton described how, ‘In the wee sma’ hours…on Saturday, the Great City of London was invaded by what was once described as a “Northern horde.” The original “Northern horde” that James Catton was referring to were Blackburn Rovers fans who followed their team to London in 1884 and 1885. They had been described by Dr. Edward Morley, a member of the Blackburn Rovers committee, as ‘an incursion of Northern Barbarians…hot blooded Lancastrians, sharp of tongue, rough and ready, of uncouth garb and speech. A tribe of Sudanese Arabs let loose in the Strand would not excite more amusement and curiosity.’ Writing in 1904, James Catton noted that Morley’s phrase was not popular. He wrote, ‘Considering that the author was a Lancashire man, and belonged to Blackburn, he might have dealt more gently with these sons of industry.’ Misrepresentations of football fans have a long history.

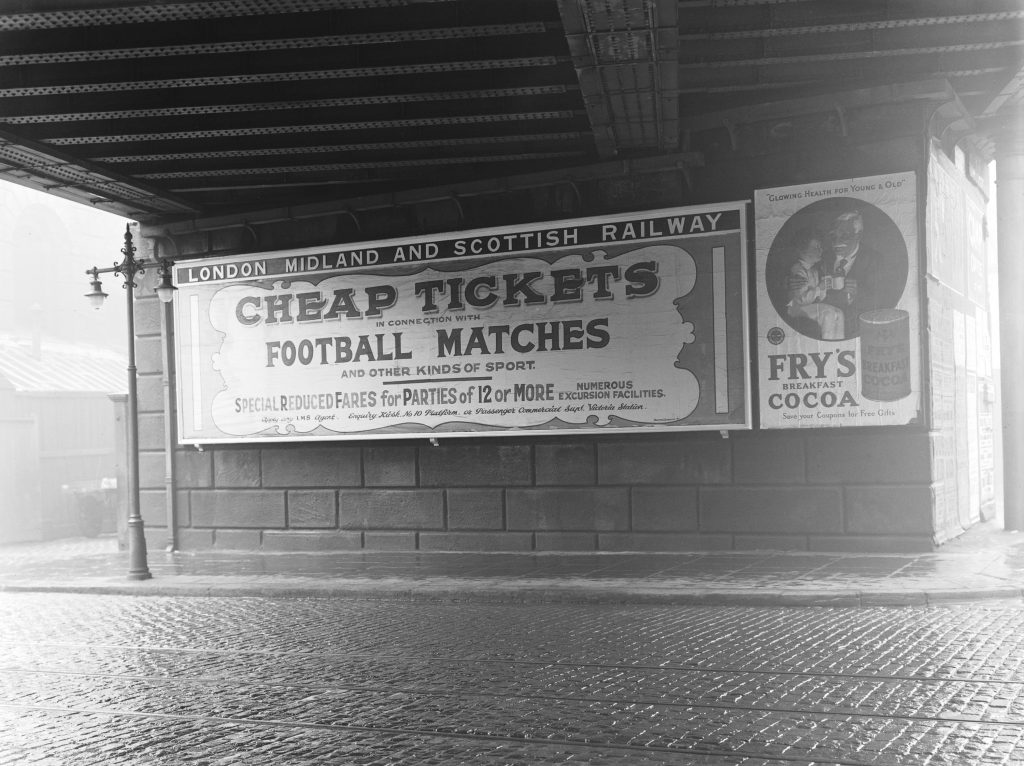

It’s easy to concentrate on the role of transport in getting colourful and noisy football fans to away games but transport played an equally important role in getting fans to home games. With the establishment of the Football League in 1888, regular Saturday afternoon football quickly became a key part of working-class leisure. By the 1905/6 season, some 5 million spectators were watching First Division matches, many of them using some form of transport to get to the game.

A lot walked but many others cycled, bused, motored, took the tram or the train across towns and cities and from surrounding districts. Special match day tram services costing 2 pence (twice the normal rate) were established in many places and by 1912 Sheffield was considered behind the times for not having one. Transport, and trains in particular, were important in spreading support beyond the immediate city boundaries. By the 1890s Aston Villa were drawing supporters from across the Black Country while Sunderland were arranging with the North Eastern Railway company to provide cheap excursions from the mining towns of County Durham. By 1906 travelling to home games was an ordinary, everyday experience.

Travelling to games further afield was rarer. The cost of travel and the challenges of getting additional time off work meant that fans did not travel every fortnight but instead chose selectively. Local derbies over short distances were popular and some clubs would organise an annual trip to a game further afield.

It was the FA cup though where most fans and railway companies focused their attention. Club supporters would travel in ever increasing numbers as their team progressed through the tournament and the final saw fans from across the country travel to London. Many of them would save throughout the year just to afford the cost of the journey to London. Even if their club was knocked out, they travelled anyway to enjoy the spectacle. For many it was their first time to the capital and sight-seeing trips were popular. Not all northerners were impressed with what they found though. In 1910, The Times described how one female Barnsley fan complained to her sweetheart, ‘Why can’t they be neighbourly?” “Nobody’s neighbours i’ London,” said her young man. “Tha’s coom to wrong shop for that lass.”

Many cup final reports stressed the good humour and behaviour of the crowds but this was not always the case. The ability of train companies to transport fans to big cup-ties sometimes exceeded the capacity of stadiums to host them, leading to rowdy scenes. In 1893, when the Wolverhampton Wanderers verses Everton FA cup final was held at Manchester, between 45,000 and 60,000 fans swamped the Fallowfield stadium. Fans spilled into the pitch and some of those unable to see threw stones at those in front. In a quarter-final replay in Leeds in 1912, the crowd broke down the gates with thousands getting in free. At the same time a criminal gang who had travelled from London attempted to steal the gate money.

As today, some fans on a day-out could misbehave. The visits of Woolwich Arsenal supporters to Leicester and Nottingham in the 1900s were accompanied by drunkenness, vandalism, petty theft, throwing home-made fireworks and one occasion, the stealing of a public-tramcar! No wonder one Leicester paper complained that, ‘no savages could have behaved with more utter disrespect for all the decencies of life.’

At the same time, well-behaved football fans could be criticised simply for going to the game. For some critics, cup final crowds were a sign of Imperial decline. In 1910, when Newcastle United faced Barnsley, the London Morning Post griped that, ‘A Cup Tie match is disquieting; it suggests of the days of the decline of another Empire when a corrupted citizens clamoured for free food and circuses.’

However, football fans were represented (or misrepresented), their mere presence was testimony to the impact that trains and transport had on the development of professional football. As the two grew up together, they helped forge the modern commercial game and patterns and traditions of spectator behaviour that are still with us today.

The National Football Museum is the world’s biggest football museum, telling the stories of the game of our lives. It’s open daily and situated in Manchester city centre.

Bibliography

Tony Mason, Association Football and English Society, 1863-1915 (1980)

Dave Russell, Football and the English (1997)

Mark Andrews, The Crowd at Woolwich Arsenal (2012)

Stuart Hibberd, Ian Beven, Michael Gilbert, To the Palace for the Cup: An Affectionate History of Football at the Crystal Palace (1999)

Athletic News (British Newspaper Archive)