2023 has been a milestone year for one of the Science and Industry Museum’s most iconic objects. The Small-Scale Experimental Machine, better known as ‘Baby’, was the first stored program computer and the predecessor of the computers, phones and tablets we’re so familiar with today.

Baby successfully ran its first computer programme on 21 June 1948, and celebrated its 75th birthday this year. The original Baby computer was built at the University of Manchester with technology used in Second World War radar and communications equipment. The work done by Manchester scientists and engineers put the city at the forefront of a global technological revolution, and it continues to be a pioneer in computer science today.

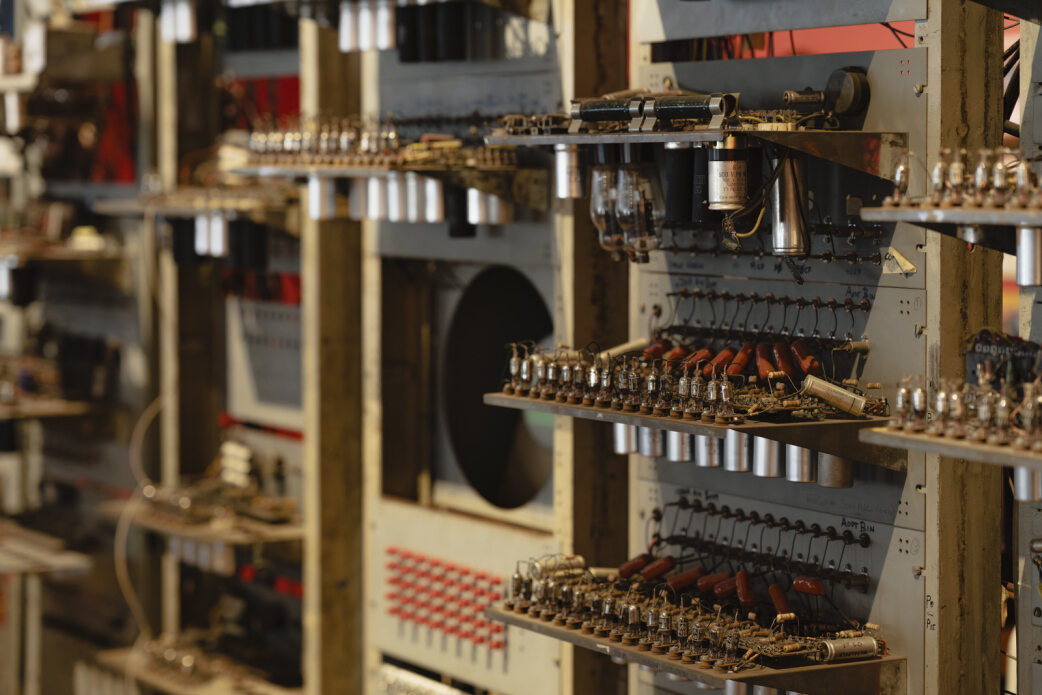

Our replica Baby, which is on display for visitors to explore, was built in 1998, using vintage electronic components and with guidance from the original designers. The original no longer exists, so this is the closest you’ll get to an important piece of computing history. The replica turned 25 this year, having been built to mark the original Baby’s 50th anniversary in 1998. It has been lovingly cared for and operated for a quarter of a century by a team of dedicated volunteers who demonstrate the machine to visitors.

In March this year, the vitally important impact Baby had on developments in computing was reaffirmed when the Government announced the new Manchester Prize—an annual £1m prize for AI innovation—and named it in recognition of the city’s status as the birthplace of modern computing. When the Prize officially launched in December, Viscount Camrose, Minister for AI and Intellectual Property, visited the museum to explore the machine that started it all.

Like many successful experiments, Baby inspired many subsequent ideas and inventions. Mathematician Alan Turing was one of the machine’s earliest programmers, an experience that no doubt influenced his 1950 article ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’, which helped lay the foundations for what we now call Artificial Intelligence.

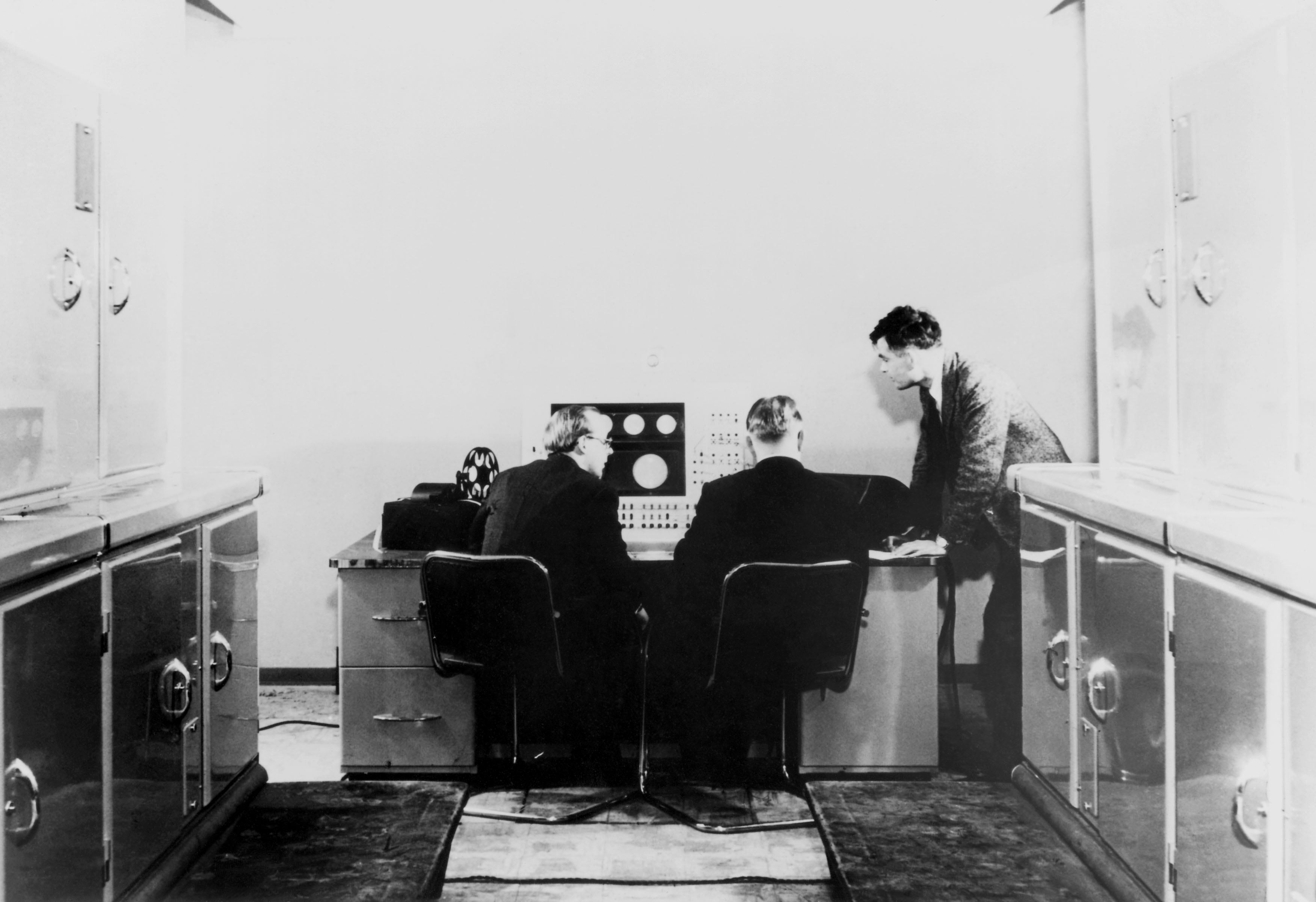

Baby grew up into a more powerful computer, the Manchester Mark 1, which local engineering company Ferranti took as the design for the world’s first commercial computer that companies could buy, the Ferranti Mark 1. Mary-Lee Woods and Conway Berners-Lee, parents of World Wide Web inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, met while Mary-Lee was a Ferranti Mark 1 programmer in Manchester and Conway was visiting from Ferranti’s London offices.

Dietrich Prinz and Christopher Strachey used the Mark 1 to program some of the first computer games, to play draughts and chess, and in an appropriately festive touch, during a 1951 BBC broadcast, the Mark 1 made history by hooting Christmas carols.

It can be argued that the World Wide Web, computer games, AI and electronic music have all been influenced by Baby—not bad for a machine with less processing power than a modern pocket calculator.

Baby was a first in all sorts of ways—the first stored program computer and the first computer with a display screen. Earlier calculating machines had displayed their results using things like mechanical counters, light bulbs or punch cards, but with Baby the answers glowed brightly on a cathode ray tube, which was probably borrowed from wartime radar set.

This little green screen was the first computer screen like the ones we have today. Unlike modern computers though, Baby has no fancy graphics processor. When you look at Baby’s screen you are seeing a picture of inside the machine’s memory. Each of the dots making up the image is a binary 1 or 0 being moved in and out of memory locations as Baby runs a program.

As Baby’s 75th year draws to a close, our colleagues have programmed it to display festive messages and images on its screen. Three quarters of a century after it first lit up the faces of the pioneering scientists and engineers working to make history, Baby is continuing to light up the faces of visitors at the Science and Industry Museum by spreading some festive cheer.