Please note: Electricity: The spark of life ended in April 2019. To find out what exhibitions and activities are open today, visit our What’s On section.

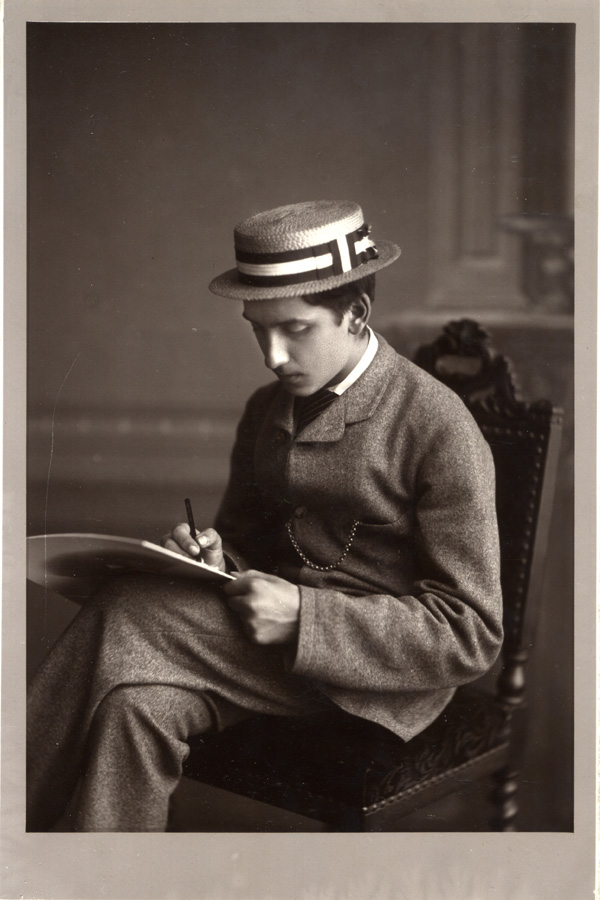

Last month on the blog, we celebrated Sebastian’s 154th birthday. This month we’re celebrating him as a child genius.

Science Museum Group Collection © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Young Sebastian (not to be confused with Li’l Sebastian, although both did receive honorary doctorates in their lifetimes) was a bit of a clever clogs. As we learned last month, his dad César was an Italian immigrant to the UK who worked as a photographer in Liverpool, while his mum Juliana was a concert pianist. Sebastian inherited his parents’ artistic nature, but he also had scientific talents.

He combined the two by making detailed sketches of his own inventions, as well as his improvements to existing feats of engineering. His interest in engineering was a bit of a mystery to his parents, whose main worry about Sebastian was that his handwriting and grasp of spelling and grammar was terrible.

From the age of 13, when he designed an arc lamp for the better lighting of streets and public spaces, Sebastian showed a keen interest in electricity. In the 1870s, Britain was just waking up to the idea that electricity might be a better way to provide lighting than gas. In 1877, César wrote a letter to his son, telling him that he was thinking of installing electric lighting in the family home. This news sparked the 14-year-old Sebastian into action.

He wrote back to his dad in May 1878, quizzing him about his lighting plan. In the letter, Sebastian describes how thrilled he is by “the thought of a pure and white light that would be so much better than gaslight”.

If César had gone ahead with his plan, he would have been ahead of the game. It wasn’t until December 1878 that Joseph Swan first demonstrated his prototype light bulb and, although he had supplied arc lamps to light the Picture Gallery in his friend William Armstrong’s house Cragside in 1878, it was another two years before his lightbulbs illuminated the first private home to be entirely lit by electricity.

Meanwhile, Sebastian had been thinking about the benefits of electricity and its potential as a source of energy to replace steam. He was on the way to his breakthrough invention and a life spent championing AC electricity.

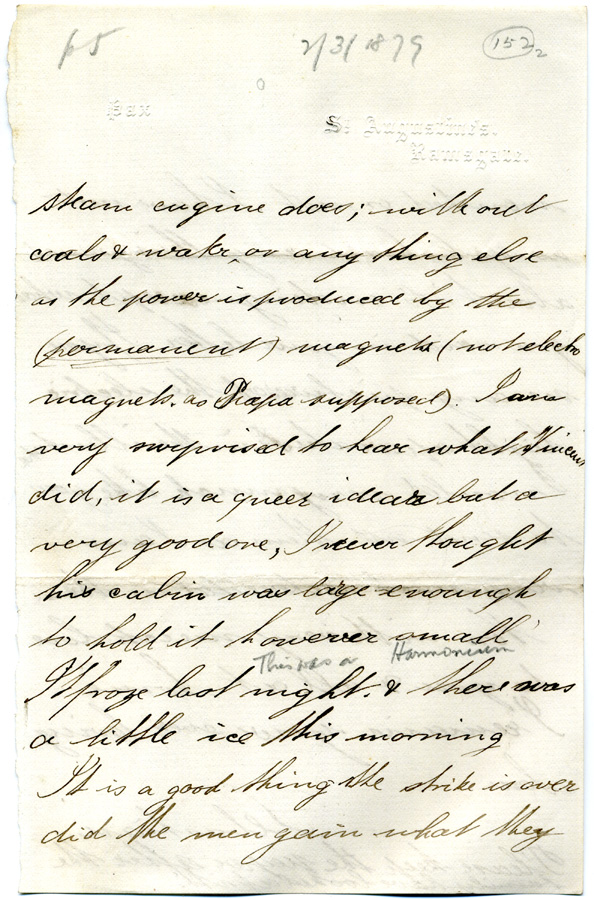

In November 1878, Sebastian wrote to his father again from St Augustine’s School in Ramsgate, where he was a pupil. His thoughts had led him to design a simple magnetic machine that could operate “without cranks, connecting rods, pistons and piston rods” and so reduce friction and the need to replace worn out parts. Not bad for a 14-year-old. Sometimes the ability to think through a challenge and find a solution makes the ability to write neatly less of an issue.

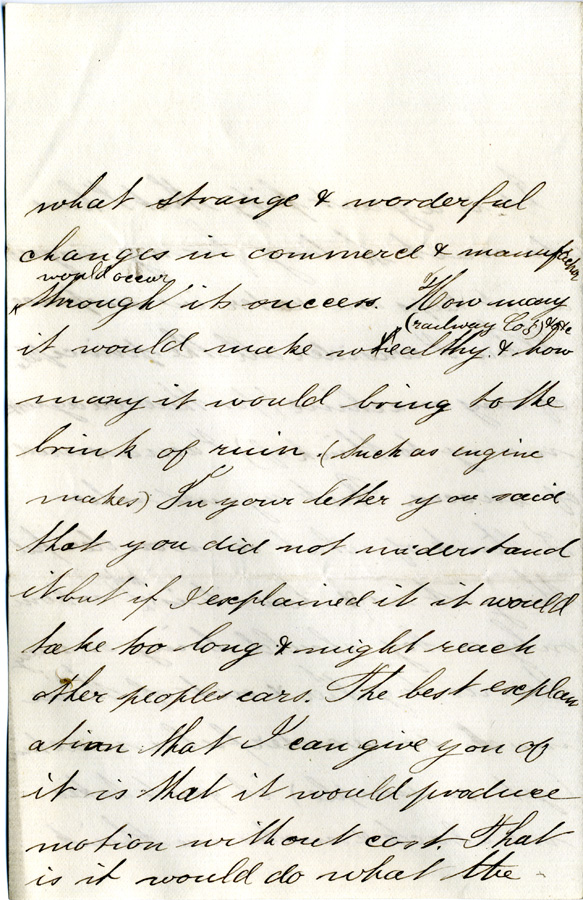

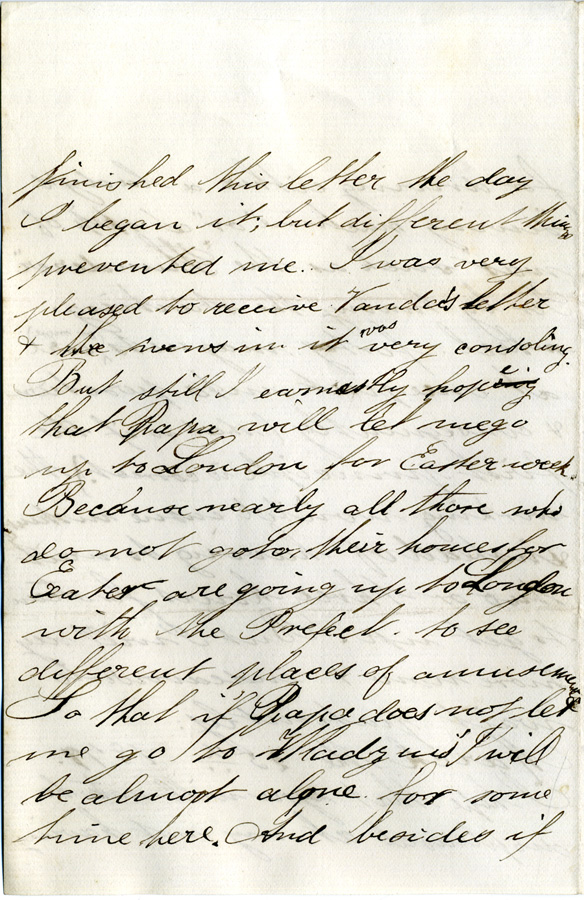

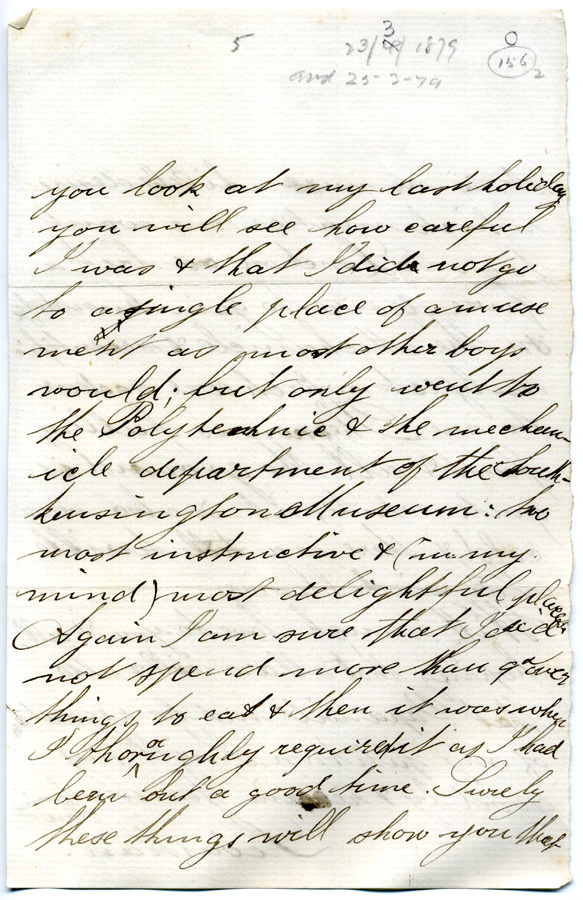

Four months later, in March 1879, Sebastian wrote to his mum. He told her that he didn’t want to explain his machine in more detail, in case the information fell into the wrong hands:

‘In your letter you said that you did not understand it but if I explained it it would take too long and might reach other people’s ears.’

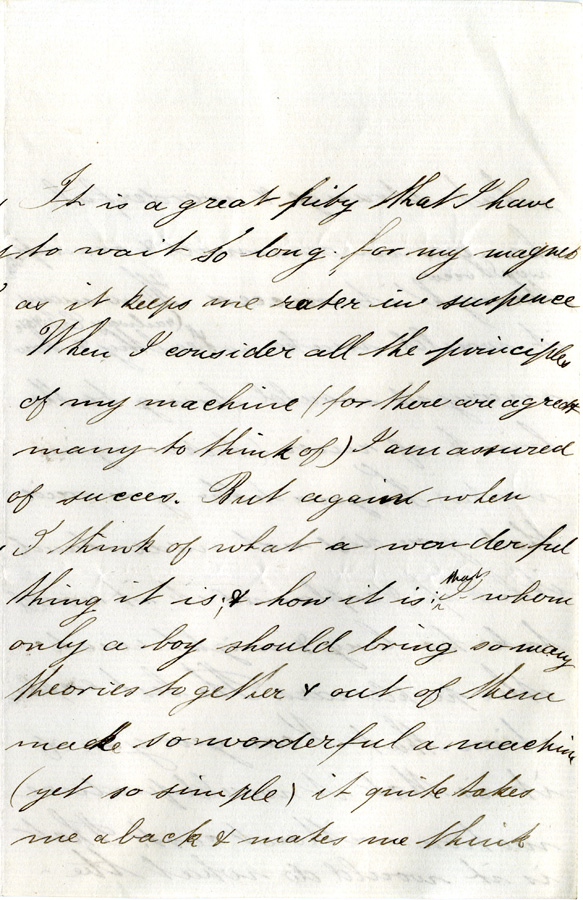

Pages from Ferranti’s letter to his mother, describing his invention

He mentioned that he was still waiting for new magnets to test his theory, and spoke of his invention with an air of wonder:

‘When I think of what a wonderful thing it is, and how it is, that I whom only a boy should bring so many theories together and out of them make so wonderful a machine (yet so simple) it quite takes me aback and makes me think what strange and wonderful changes in commerce and manufacturing would occur through its success.’

Despite knowing that his mum wouldn’t grasp what he was saying, he explained that the machine would produce power using permanent magnets rather than electromagnets.

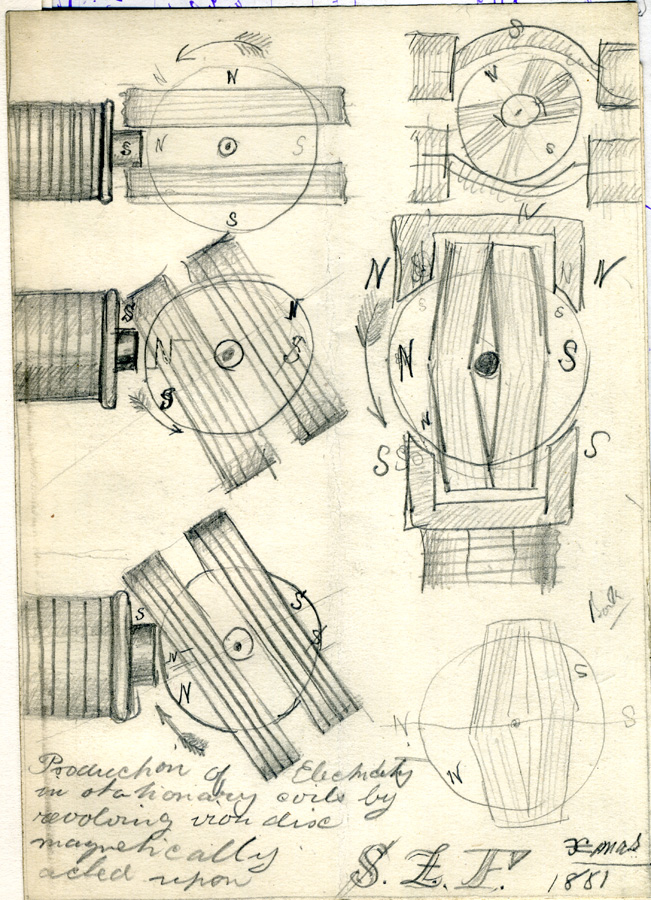

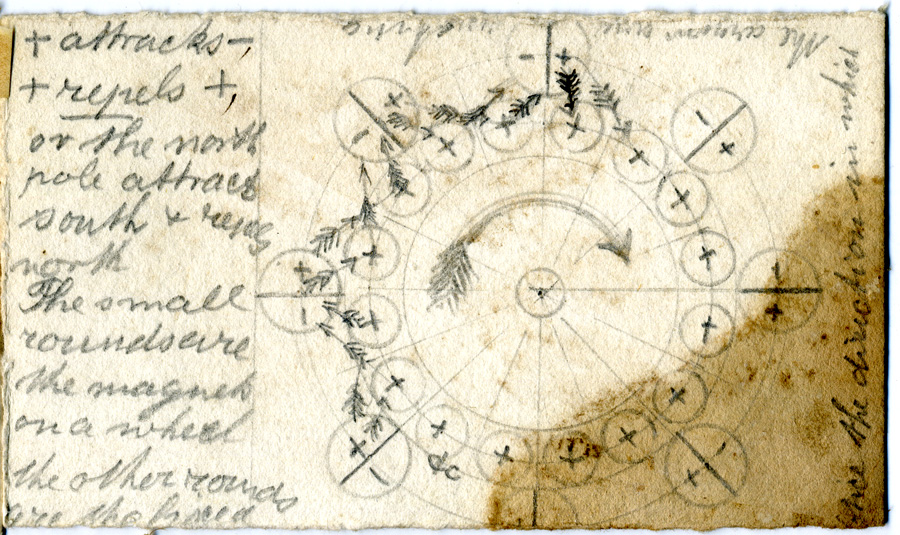

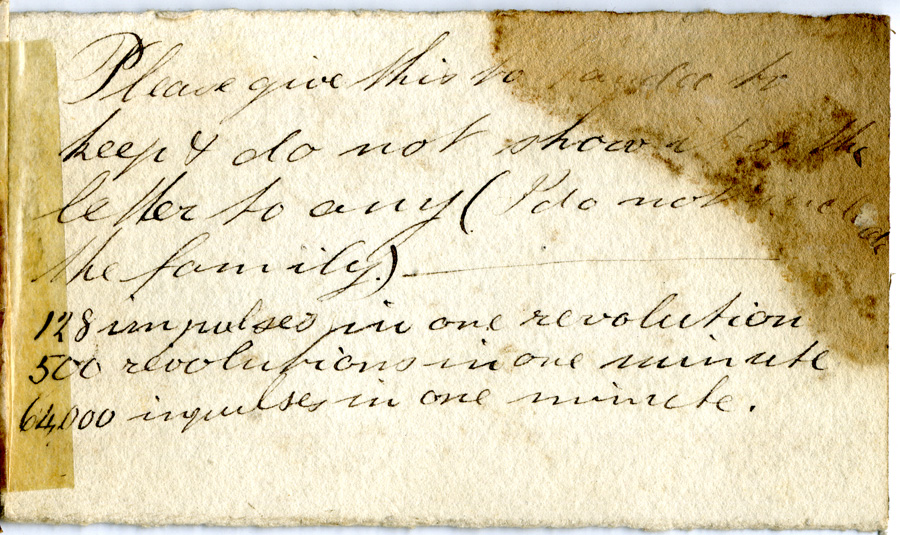

Later that month, Sebastian was so sure that his machine would work that he wrote to his half-sister Vanda, enclosing a diagram of the machine and requesting that it was not shown to anyone outside the family. He was already thinking like a businessman and trying to protect his design from competitors. He wasn’t quite 15 years old.

A diagram and letter Ferranti sent to his half-sister Vanda

Developing this machine occupied all of Sebastian’s spare time in the following years. Letters home made frequent references to his experiments and he asked for permission to spend his school holidays in London so that he could visit the London Polytechnic (now the University of Westminster) and the mechanical department of the South Kensington Museum (now the Science Museum).

Letter from Ferranti asking permission to stay in London at Easter

One year, he even asked for a book on electricity and magnetism for his Christmas present and a subscription to The Engineer.

In his final year at school, Sebastian’s teachers realised that they had taught him all that they could about engineering. His father agreed to pay for Sebastian to attend a course in engineering at University College, London. At the same time, one of his school teachers introduced Sebastian to a local electrical engineer called A J Jarman.

Mr Jarman helped Sebastian to build his magnetic machine and advised him to use electromagnets rather than permanent magnets to generate a more powerful current. Their work together resulted in Sebastian’s first AC dynamo, also called an alternator or generator. Sebastian was 16 years old. He recorded his work on the AC dynamo in his notebook.

Science Museum Group Collection © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Sebastian left school in 1881, at the age of 17. His father had suffered a blood clot on the brain in February that year. His illness affected his photographic business and the family could no longer afford to keep Sebastian in school.

This didn’t faze Sebastian, though. He finally finished his alternator and sold his first one that year. He also moved to London and joined the Experimental Department at the Siemens Brothers and Co works in Charlton. He made the most of his practical experience there, and in his spare time continued to work on his alternator.

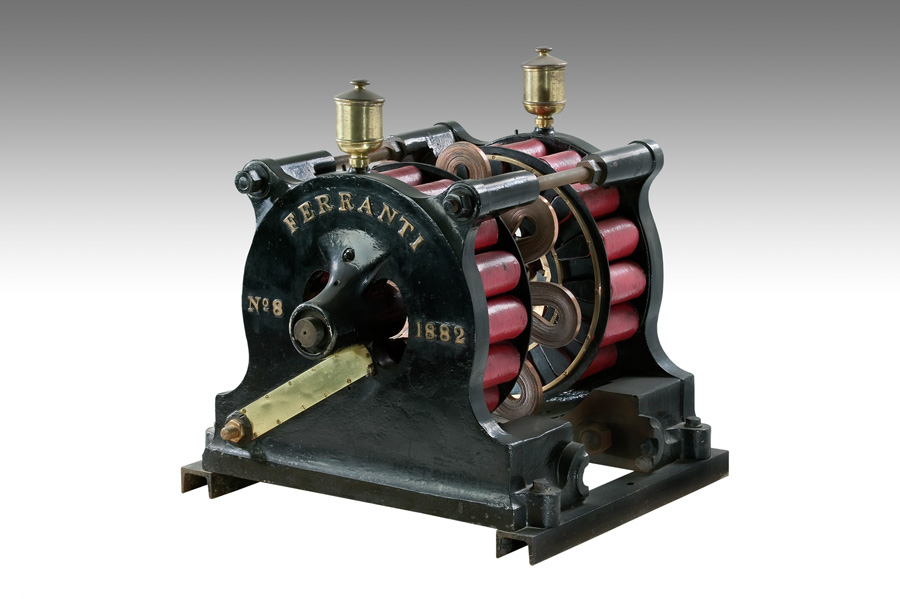

The machine coincidentally shared a revolutionary design with a dynamo that Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, had developed. Thomson was 40 years older than Sebastian, which shows what a remarkable young scientist Sebastian was. Together the two men patented the design as the Ferranti-Thomson Dynamo in 1882.

The same year, at the age of 18, Sebastian formed his first company, Ferranti, Thompson & Ince, and put the Ferranti Alternator into production.

Science Museum Group Collection © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Designing the alternator was the first of many pioneering moments in Sebastian’s career. A new exhibition, Electricity: The Spark of Life, will open at the museum in October 2018. The exhibition will present the story of electricity, the powerful force of nature whose spectacular discovery, dramatic distribution and indispensable demand has fundamentally changed our way of life.

As part of this story, we will celebrate the achievements of Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti in the field of electrical engineering. We hope to inspire other 14- to 18-year-olds to find solutions to today’s energy and engineering challenges and think about a career in STEM.

To read about the work done in Manchester by the Hopkinson brothers, on the other side of the ‘Battle of the Currents’, click here.

3 comments on “Ferranti the child genius”

Comments are closed.

Hi Jan,

Your piece on Ferranti is most perceptive so I suggest you pursue Ferranti’s own house at Baslow which is now better known as a restaurant [Fischers of Baslow]. As Baslow Hall, Calver Road it gets only a glancing reference in the Buildings of England Derbyshire volume but it obviously was one of the first ‘electric houses’ in Britain and thus worth some scientific attention. It really needs a scientific Blue Plaque.

Ian