At Tinkertastic this half-term, families have been making chain reaction machines that link together to make something happen at the end. This could be a travelling marble or pushing a block off a table. Explainer Team Leader, Dannielle Bryers, has long dreamed of bringing this activity to our audiences. Here she explains how she was inspired and what these machines can do to break down peoples ideas about engineering and physics:

The first museum exhibit that really fascinated me was a massive chain reaction machine that moves billiards balls around an apparently infinite number of possible routes at the Ontario Science Centre, in my hometown of Toronto. Children (or adults, I seem to recall my mom being pretty invested in what happened!) could control parts of the machine and choose when to introduce new balls to create different reactions – the giant xylophone was my favourite. I asked to go play with it every time we visited the science centre without realising that I was learning to understand Newton’s laws of motion, or that the name for that type of over the top contraption was a Rube Goldberg machine.

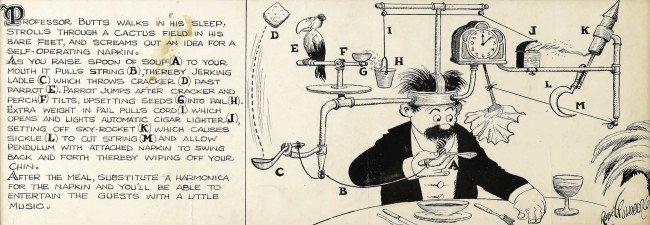

Rube Goldberg was an American cartoonist who trained as an engineer, then promptly put his energy into drawing satirical cartoons. He even won the 1948 Pullitzer prize for his political illustrations. However, his longest legacy is the series of drawings depicting Professor Butts – a character based on some of his university lecturers – who designed impossibly complicated machines to accomplish very simple functions.

Goldberg’s contemporary here in the UK was Heath Robinson, an illustrator who created cartoons of increasingly silly ‘secret weapons’ and inventions during WWI. In today’s TV and films, creations like Wallace and Gromit’s machines owe a lot to Heath Robinson and Rube Goldberg and the game Mousetrap is another great example of their influence. Since working at the Science and Industry Museum I’ve always wanted to bring our visitors in on this light-hearted, hilarious take on engineering.

A lot of thinking that goes into activities for half term is about what visitors might get out of it and whether it’s accessible to a wide range of people. For years I’ve been bringing up the idea of a chain reaction machine, then discarding it because we just couldn’t figure it out. Would different visitors contribute throughout the day, and we set it off at the end? But then there’s not payoff for most of the people who contribute. Do we build one ahead of time, then prescribe what people have to do? Then there isn’t any creativity, even if it is a really fun toy. When we decided on tinkering as a theme of activities for May half term, my colleague Joe got stuck into some research and found a guide to collaborative chain reaction machines on the Exploratorium’s website where they graciously share loads of lessons learned. There it was – the key to getting complete strangers of totally different ages and backgrounds on the same page to make up a brand new machine. Joe modified things slightly (no power tools I’m afraid folks!), but teams need to work together to figure out how they’ll pass the power on to each other, then work on their own discrete way of moving it between points. Some groups have gone as simple as dominoes moving across a table, others have built pulleys that activate a swinging ball that knocks another ball down a ramp and pushes a car into the first team’s dominoes.

Most of the machines that we still run at the museum, like our Lancashire Loom, operate on the same principle as a Rube Goldberg machine, albeit with a little bit more purpose. On the loom, as a cam pushes a lever to send the shuttle that carries the thread across the width of the fabric, another is moving the warp threads apart so the shuttle can fly through, while a series of cogs is advancing the fabric by millimeters and a tiny balanced weft fork is reading whether the thread in the shuttle has run out. All of those actions happen in about 1/3 of a second, so it’s a lot more closely engineered than our plasticine and toy car machines, but the principle holds: Pass on the power to create a series of actions and reactions. The idea of engineering holds too – in 45-minute sessions we’re playing, revising and improving ideas just as professional engineers do. Everyone is absorbing lessons about the 3 laws of motion and perseverance in the face of failure. Our hope is that most of all they’re having a brilliant time making the silliest, most ridiculous machine possible.

Very well done! And I would say that even if I wasn’t your Dad.

I am proud of you.