The rise of COVID-19 is consistent with Earth’s response to the burgeoning human population, now more than 7.5 billion people, according to James Lovelock, our most famous independent scientist.

Lovelock is best known for his Gaia Hypothesis, which views Earth as a self-regulating system, such that, as the global population rises, so does the opportunity for pandemics to arise.

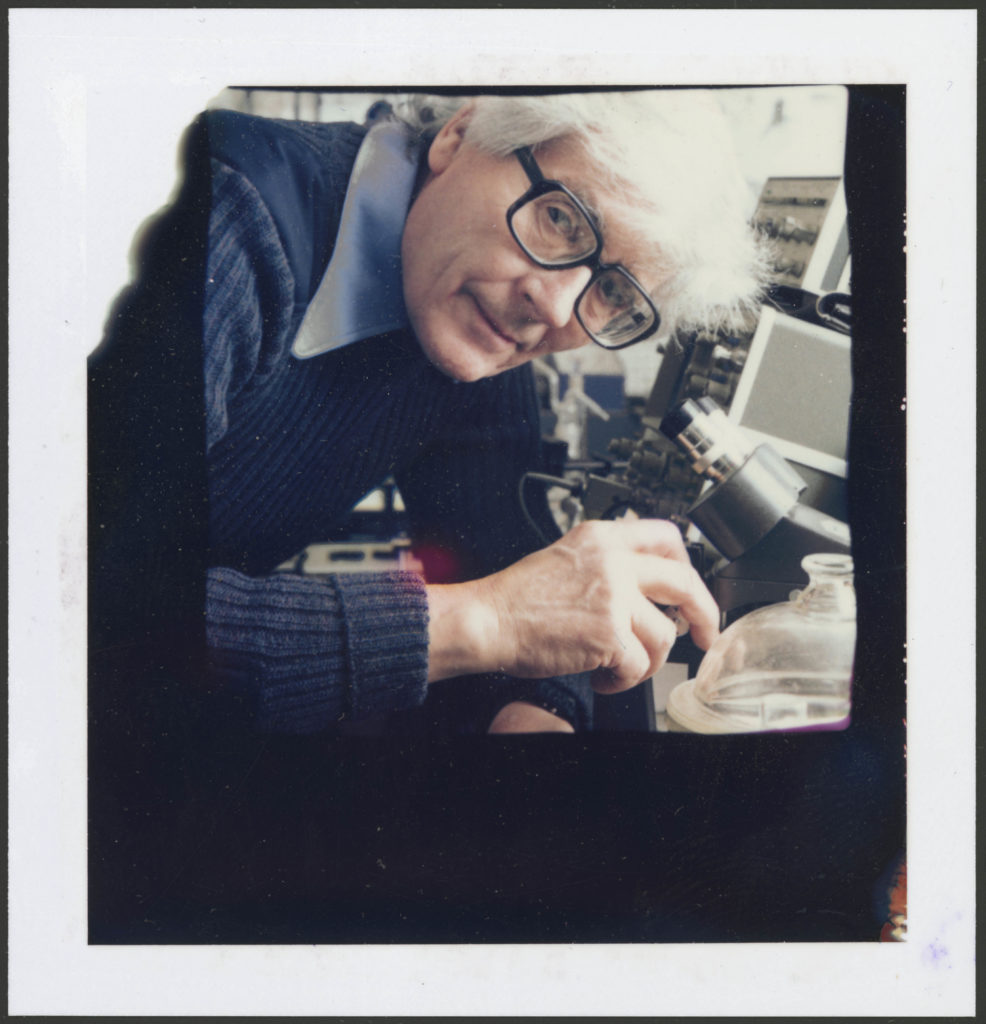

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

A recent study concluded that spillovers of animal viruses into humans—such as COVID-19—are becoming more likely as a result of how humanity is changing land use.

Climate change poses an even greater threat than the pandemic and, if we do not curb global heating, we will find ourselves removed from the planet, said Lovelock, 101, who recorded a series of provocations with me at his home near Chesil Beach for a special online event at the Manchester Science Festival (12–21 February).

Physicist, oceanographer and broadcaster, Dr Helen Czerski, will lead the discussion of his provocations on February 13 with our expert panellists, including science writer and broadcaster Gaia Vince, climate activist Prof Chris Rapley, CBE, and Zamzam Ibrahim, Vice President of European Students’ Union.

Lovelock has a special relationship with Manchester, where he graduated as a chemist from the University of Manchester in 1941.

Lovelock only picked Manchester after he had visited a youth hostel in the Lake District in 1939, where he became smitten with Lois Dickinson, a chemistry student at the university.

His love was unrequited, but Lovelock found that Manchester proved the ideal university for his studies.

Lovelock took an honours degree in chemistry under Alexander Todd, also studying physics under Patrick Blackett. Both were young and dynamic, with Blackett going on to win a Nobel prize in 1948 for his work on cosmic rays, and Todd in 1957 for his work on the building blocks of biochemistry.

However, Lovelock almost came unstuck a few weeks into the course when Todd accused him of cheating in a chemical analysis, producing suspiciously right answers.

Lovelock countered that he could almost do this analysis in his sleep, as it had been an important part of his work for Murray, Bull and Spencer, a firm of consultants in southwest London that he had joined in 1938. The firm had paid for him to study at Birkbeck College, which had paved the way for his studies in Manchester.

Over his extraordinary career, James Lovelock has come a long way since he was inspired by a visit to the Science Museum in 1925, which he found ‘a major source of inspiration’ and more useful than classroom learning.

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

He joined the Medical Research Council’s National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill, London, after he graduated from Manchester. While working there, he had an unusual encounter with Stephen Hawking.

After he resigned from the MRC in 1961 he went, at the invitation of NASA’s Director of Spaceflight Operations, to work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena on equipment to land on Mars and the Moon to analyse the surface. At the same time, he was given a tenured post as a full professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

Lovelock did not go fully independent until 1965 when he resigned from Baylor and returned to England. As an independent scientist, Loveock worked for NASA, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Hewlett-Packard, Chemical Manufacturers Association, Ministry of Defence, Pye Unicam and the Shell Oil Company.

From Gaia to searching for life on Mars to speculating about living with cyborgs in Novacene, his latest book, Lovelock occupies an extraordinary place in the last century of science as a truly independent researcher for most of his working life, regarding himself as ‘half a scientist, half an inventor.’

In 2012, the Science Museum Group acquired Lovelock’s archive, consisting of 84 boxes of notebooks, manuscripts photographs and correspondence.

Two years later, I talked to him about his life and the importance of his electron capture detector (ECD), a remarkably sensitive instrument to detect trace amounts of chemicals that helped to hone his thinking about Gaia, his holistic view of the world as a super-organism.

He worked on the theory with the American biologist Lynn Margulis, and his friend, novelist William Golding came up with the catchy title of Gaia, the ancient Greek for Earth, in 1972.

We discussed the opposition Gaia faced in the early days, notably from the biologist Richard Dawkins, and how he had devised his Daisyworld computer model to show his critics that it is indeed conceivable for a planet’s life to regulate its own climate.

In Daisyworld, Lovelock showed how life could evolve to help Earth keep its cool, in spite of our warming sun. To keep his model simple, he populated it with black daisies that absorb heat and white ones to reflect it.

The dark- and light-coloured daisies evolved within this idealised world, waxing and waning to balance the way they absorbed and reflected sunlight to regulate the temperature, so it was optimum for plant growth.

You can see printouts of his Daisyworld model in the Science Museum Group collection.

Lovelock was also a Visiting Professor at Reading University from l965 until retirement age, awarded honorary degrees by various universities, and was a council member of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Plymouth and its President for four years. ‘It was a busy life and still goes on,’ he told me this week.

Prof Rapley of UCL, who has worked with Lovelock, commented:

“Jim Lovelock is one of the most original thinkers of our age. His concept of Earth as the superorganism Gaia shifted the perception of life as merely a passenger to being a primary core actor on our celestial spaceship and laid the foundations of the new discipline of Earth System science. At the age of 101 he remains the Guru of the field, revered by its most celebrated proponents.”

Earth, but not as we know it: Lovelock’s legacy and our future is available to watch online now.